Beginning the Roaring 20s Quintets – Small Steps

A Prelude

The original 2016 thesis behind our exploration of woodwind quintets of the 1920s was that there was an uncharacteristically sudden interest in writing for this ensemble during this decade. The quality of five of those compositions by Nielsen, Hindemith, Schoenberg, Villa-Lobos and Ibert was so good that they have been steadily performed, even a century later. Two other works by Lorenzo Fernandez and Blumer, were much harder to find for much of the twentieth century, but are now being revived. Further, these quintets, each in a different style, showed how modern composers could use their quintets to explore new ideas, and possibly explore new expressive techniques. There was a historical turning point here that made the woodwind quintet much more popular to composers, performers and audiences.

In almost a decade since I researched that original thesis, I discovered I was wrong about the number of compositions for woodwind quintet written at that decade. I thought I could find a few more that I missed back then, but when I did a systematic search for more quintet composers of the 1920s I found 49 additional composers who wrote 51 woodwind quintets during those years! So instead of disproving my original idea, each new piece helps confirm the original thesis.

So I decided to further investigate each of these 49 composers. A few are almost invisible on the internet and, indeed, to music history: for them there isn’t much new information to be found. Others have loads of biographical and other information available and I learned a lot about them, their compositions, and sometimes got an idea about their contribution to the melange of musical styles of the 1920s and in musical history since then. Each new work I listened to gave a newer perspective of the competing musical styles of the early 20th century.

So, here is that research in many blog posts. Unlike the original series, I’ve found works for each year from 1920 onwards. But there was a steady accelerando in the number of works being composed throughout the decade. With the addition of works from 1920 and 1921, the project has grown to eleven years.

Another interesting thing I found is that almost every composer on the list soon had their career affected by the Great Depression and by the build-up to and the actual events of World War II. Many Jewish and progressive artists were banned and forced to leave Germany before World War II or face arrest. At least one of our 1920s quintet composers was killed in the Nazi concentration camps, others survived. Some served in the armed forces (on either side). One had his home destroyed by a German bombing raid and another lost much of his work in an allied bomb strike. Others spent considerable time and effort to leave their homes, most often moving to Paris, southern France, Portugal, England, or Switzerland to escape the Nazis (with varying success), and many left Europe altogether – the lucky ones moving to the United States (New York, Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles were the favored cities). Others remained behind.

It was obvious to most people by 1933, at least in Germany and Austria (and soon after in Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia), that opposing the Nazi Party and Adolf Hitler was bad for your health and livelihood. You didn’t have to be Jewish, but being Jewish or descended from Jews, could be lethal. If you wanted any career in Germany and Austria, even in music, you likely joined the Nazi Party: some supported Hitler and others feared him. (Likewise in Spain and Italy, opposing Franco or Mussolini was dangerous.) Many composer biographies completely black out the years 1939 to 1945 and skip to what they did after the war (if they were lucky enough to survive it). In Eastern Europe after the war, being a progressive artist was still difficult under the Communists, but not necessarily lethal.

In any case, if I learned a composer joined the Nazi Party, I mention it. You and I might not want to perform a work by such a composer, but ultimately it’s your choice.

So, since I was dividing the list up by year, I decided to also include some historical highlights for each year (1920-1930). Some were fun facts: such as the lists of a few popular tunes in each year. Some showed how science and technology were changing the world, especially in communications and in the consumption of music. I don’t think any composer or musician in the 1920s would have predicted World War II, but there were events in the 1920s that effected how the war came to be and how it turned out. (That’s a fascinating thing about history.)

Enough, let’s get this show on the road.

1920 – News Highlights

- The world-wide flu pandemic, of 1918-1919 was now over after killing at least 50 million people world-wide, more fatalities than in World War I.

- The League of Nations is created. The U.S. never joins, however.

- The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (later known as the NAZI party) is founded in Munich.

- U.S. women earn the right to vote.

- The first commercially licensed radio station was KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- The last American troops return from Europe after World War I.

- Prohibition begins in the United States; alcoholic beverages are illegal throughout the 1920s into the ‘30s.

- The first complete performance of Holst’s The Planets was performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.

- Mamie Smith’s first blues recordings become a hit; record companies suddenly discover an African-American market.

- Al Jolson records “Swanee” for Columbia Records.

- Ballets: Milhaud writes Le Boeuf sur le toit; Stravinsky writes Pulcinella.

- Popular Music: “Down By The O-HI-O (I’ve Got The Sweetest Little O, My! O! )” by Jack Yellen and Abe Olma; “I’ll See You In C-U-B-A” by Irving Berlin; “Look for the Silver Lining” by B. G. DeSylva and Jerome Kern; “My Mammy” by Sam M. Lewis, Joe Young and Walter Donaldson.

There are only two very short works for woodwind quintet written in 1920 by Henri Maréchal and Lodewijk Mortelmans.

Maréchal, Henri (1842-1924)

.

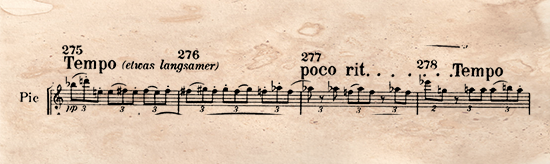

Maréchal’s small contribution to woodwind quintet literature was Air du guet, Provençal theme attributed to King René (1409-1480), written in 1920. The original printing was by Heugel, in Paris, in 1920. A modern edition is available from TrevCo Music Publishing, in Tallevast, Florida.

Score and parts of the Heugel edition are now available for download from the International Music Score Library Project. Alternatively, the same files can be downloaded from JR Research at the University of Rochester.

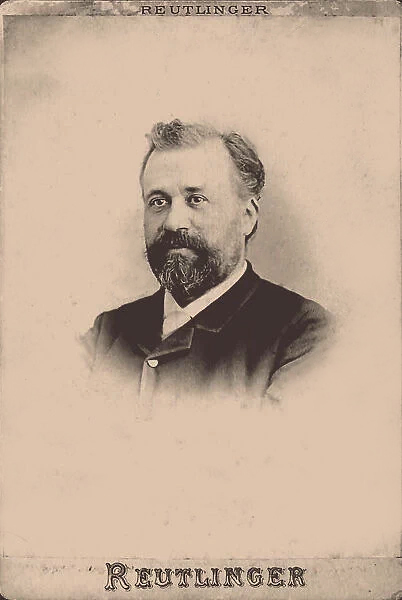

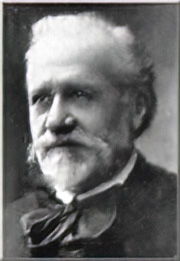

Henri Marèchal was primarily a composer of operas and vocal music, and we have no explanation about why the aging, 68-year-old composer would suddenly write one woodwind quintet in 1920. The theme of the work is attributed to King René, the same monarch referenced in Darius Milhaud’s La Cheminée du Roi René in 1939.

As a student at the Conservatoire de Paris, Maréchal, in 1870, shared the Prix de Rome with Charles Edouard Lefebvre (who in 1884 wrote his own woodwind quintet). Even as Maréchal’s work is easily available in print or as a download, there appears to be no recording of the work available online or commercially. A brief biography of Maréchal (in French), on a list of Prix de Rome winners, includes a link to a truly awful synthesized realization of the quintet. It’s a short work, so some quintet would do us a favor to post a recording of their performance online just so we could evaluate it fairly.

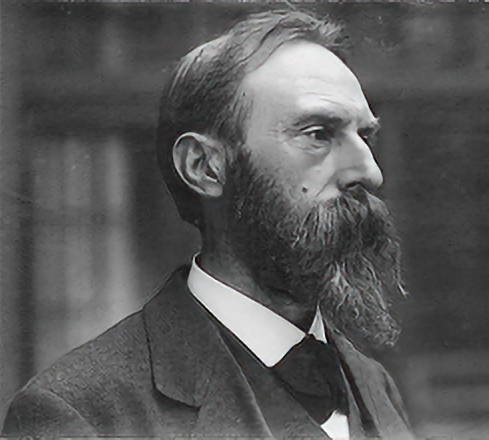

Mortelmans, Lodewijk (1868-1952)

Eenzame Herder – Berger Solitaire (Der einsame Hirte) (1920)

The original publication of Eenzame Herder was by Metropolis Editions in Antwerp. It was subsequently published by Le Centre Belge de Documentation Musicale (CeBeDeM) in Bruxelles, which closed shop in 2015.

Born in Antwerp, Belgium, Mortelmans studied music at the Royal Flemish Conservatory winning the Belgian Prix de Rome. From 1901, Mortelmans taught counterpoint and fugue at his alma mater, and became Director of the Conservatory in 1924. Among his students we find Marinus De Jong who later wrote several woodwind quintets. As a composer, he is mostly remembered for his orchestra works, songs, and other works for voice. His symphonic works reportedly hearken back to the early Romantics (such as Brahms), but he was a bit more adventurous with his songs. But, once again, we have no information about the circumstances of the composition of his only chamber music for winds. Eenzame Herder (which translates roughly as The Lonely Herder) was written in three versions, one for woodwind quintet, one for wind septet (flute, oboe, 2 clarinets, bassoon and 2 horns), and another for piano. The piano version is the only one I’ve found available online for listening. A quick listen to the piano version of this work reveals it to be a short, pensive (if not sad) work in 12/8 time in A minor. The septet version was published by Metropolis Editions in Antwerp. Mortelmans retired and in his last 20 years moved to the countryside and composed.

Unlike many other composers on this list, Mortelmans had already retired into the Belgian countryside by World War II. We have no biographical information for those years, but the German occupation of Belgium (whose King surrendered early in the conflict), was likely no picnic. Mortelmans and his wife survived the war, although the country had a long period of recovery from it.

Probably the best online biography of Lodewijk Mortelmans is on a website dedicated to him and his artist brother, Frans, and some other Mortelmans.

This series continues. Next 1921…

Credits

The engraving of a younger Henri Marèchal was printed by an engraving company by the name of Reutlinger. Available from Wikimedia.

The photograph of an older Marèchal is also available from Wikimedia.

The photo of Lodewijk Mortelmans and his impressive moustache and beard is from www.lodewijkmortelmans.be website (link above).

Copyright © 2024 by Andrew Brandt