Towards a New Type of Woodwind Quintet

Hindemith’s Early Life

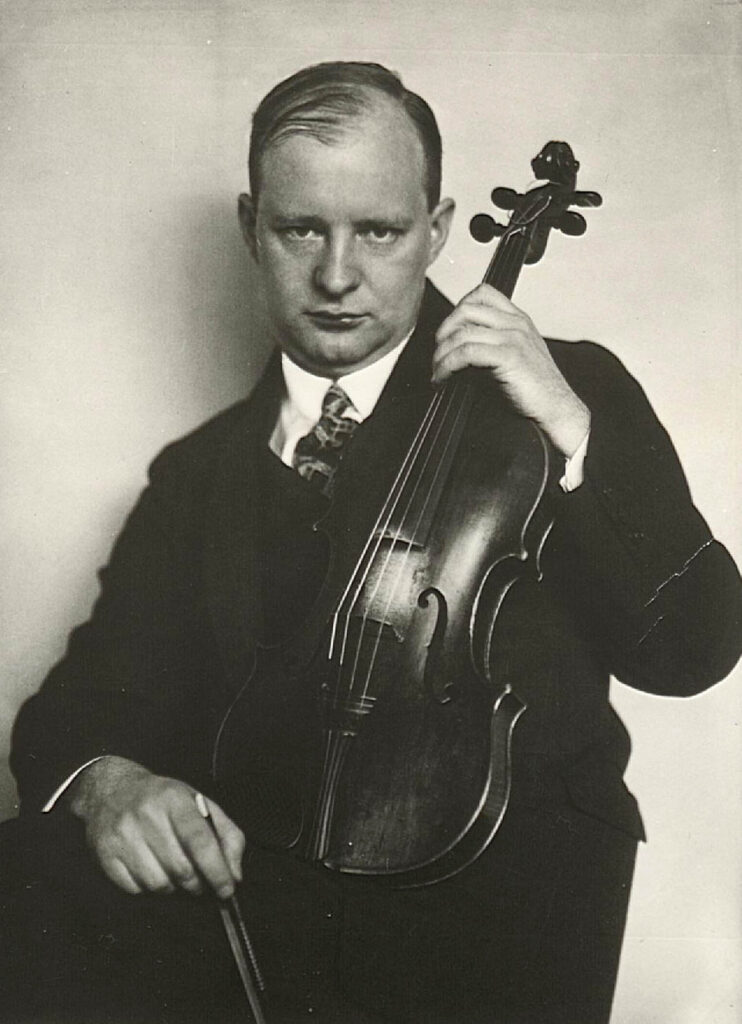

Paul Hindemith was born to a poor family in Hanau, near Frankfurt in 1895. His father was part of a family of music-lovers, but was frustrated at his lack of success: first in music and later as a painter. As a result, he required his three children to study hard to be professional musicians: Paul on violin, his sister Toni on piano, and his brother Rudolf on cello. At the age of 12, Paul began studies with Adolf Rebner who was leader of the Frankfurt Opera orchestra, a chamber musician and a teacher at the local Conservatory. Hindemith concentrated on violin and later began composition studies. (He would later switch from violin to viola as his principal instrument.) His earliest compositions, unpublished in his lifetime, were late Romantic style works.

In 1914, Hindemith joined the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra and soon became its leader, where he met many of the leading German conductors who would later champion his work. Hindemith also was very busy as a composer. He embraced Expressionism until the 1920s, when he was drawn to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, which believed that the style of a work should adjust to its chosen function and character, but still allowed a wide variety of styles. His woodwind quintet is described as being both a result of Neue Sachlichkeit and Gebrauchsmusik.

Listening to his most popular works today, in 2024, it’s almost a surprise to learn that Paul Hindemith was considered one of the most progressive composers of Germany in the inter-war years. He was also one of the most influential musical theorists and teachers of the early twentieth century as well.

It almost didn’t come to be. World War I interrupted Hindemith’s term with the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. He was drafted into the German Army in 1918, towards the end of World War I. At first, he was assigned to play bass drum in a regimental band and form a string quartet. But in May of that year his unit was sent to the front in Flanders where he writes of dodging bullets on the way to quartet concerts. He also served as a sentry; his diary records him surviving a grenade attack only by a miracle.

Still, by 1922, Hindemith was known more as a performer than as a composer. That year found him writing the beginning of a series of works he titled, Kammermusik (Chamber Music), later described as Hindemith’s equivalent to Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. The first work of that series, which shares an opus number with his quintet, Kammermusik No.1 (Op.24, No.1) was for a larger ensemble (flute, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, harmonium, piano, string quintet and percussion, including an air raid siren) and allowed Hindemith to experiment with new textures and timbres. (It could easily be slipped into a 21st century modern music concert, as well as alongside the progressive works of his contemporaries, Schoenberg and Webern in Germany, and Igor Stravinsky (whose Le Sacre du Printemps was written nine years earlier).

For the curious, there is a wonderful recording of Kammermusik No. 1 by members of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra on YouTube, accompanied by hypnotizing experimental video by early photography pioneers, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and René Clair.

The Quintet

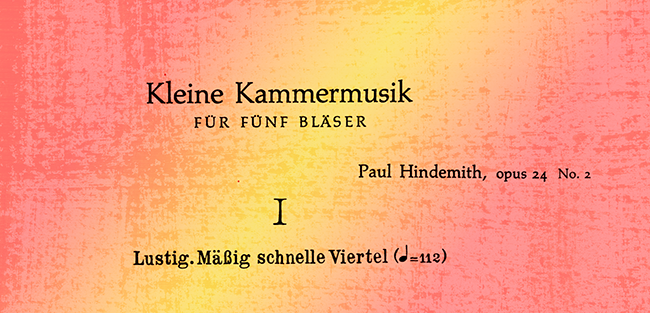

Compared to Op. 24, No. 1, Hindemith’s woodwind quintet, Kleine Kammermusic, Op. 24, No. 2, seems almost tame. It was written for his orchestral colleagues in the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra, who had formed the Frankfürter-Bläser-Kammermusikvereinigung (The Frankfurt Wind Chamber Music Society). They performed the premiere performance of the work on June 12, 1922, at the second Rhenish Chamber Music Festival in Cologne. It was published by B. Schott’s Söhne, where it is still available today.

The movements of Kleine Kammermusik are:

- Lustig. Mäßig schnell Viertel

Walzer: Durchweg sehr leise

Ruhig und einfach

Schnelle Viertel

Sehr lebhaft

The work uses the standard woodwind quintet but requires the flutist to play piccolo in the second movement.

In the first few bars of the opening movement, Hindemith quickly stakes his claim for creating a totally new approach to writing for the woodwind quintet. The clarinet solo in the beginning covers all-twelve of the chromatic tones in the first five bars, demonstrating a new chromatic exploration of melody and harmony. Soon, we also see that, compared to most earlier woodwind quintets, there is also an emphasis on polyphony and solo colors, often on top of ostinatos in the other instruments. Rather than employing tutti orchestration, he often reduces the accompaniment to allow solo instruments to be heard clearly. So when he does have all the players together, it has more dramatic effect. (This is nothing new to modern scoring, but it is a departure from many of the Romantic-period woodwind quintets.)

Curiously, both Hindemith and Schoenberg (in his soon-to-be quintet) modeled their second movements after a Waltz, although each of them were unlike any waltz composed up until this time. Hindemith’s waltz, making use of the piccolo, features solo lines with light accompaniment, achieving a clarity in sound and a succinctness in form – again in total contrast with woodwind writing of the past.

Hindemith’s third movement sounds, to these ears, like an elegy, not a surprise from a composer who served on the front lines during the end of the World War. With a slower tempo, the march-like middle section could be heard as a ghostly march of now-gone souls of friends and colleagues (which reappears in the coda). (If you also ascribe the idea of an elegy, Hindemith would not be the only composer remembering lost colleagues. In France, each of the six movements in Ravel’s original Le Tombeau de Couperin were dedicated to friends who fell in the war. The work is now a popular quintet in its various arrangements. See our list of Ravel quintet arrangements. Perhaps the works could be combined in a concert theme of music by veterans.)

Returning to the theme of emphasizing the unique timbre and solo abilities of each member of the woodwind quintet, the fourth movement features short cadenzas for each instrument. A model of brevity, the movement is only 23 bars long and last less than a minute.

The energetic finale sounds march-like, even as it slides between 6/4 and 9/4 meters. This movement has a dramatic drive that ends with the entire ensemble in rhythmic unity with a virtuosic display that continues to impress today.

For audiences (and quintet players) in 1922, who grew up listening to music in the Romantic style (a style not yet dead, as we will see in Theodore Blumer’s Quintet), Hindemith’s quintet was revolutionary in almost every way. This was only the first of several innovative works written for woodwind quintet in this decade.

Hindemith’s Other Music for Winds

Hindemith never wrote another woodwind quintet. He did write 26 solo sonatas (with piano accompaniment) for various instruments, including flute, oboe, English horn, bassoon, clarinet and horn.

His Septet, composed in 1948, is for flute, oboe, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon, horn and trumpet, and it’s a bit surprising more quintets haven’t branched out to perform the piece. There are also two Quintets for Clarinet and String Quartet (1923 and 1945) and other assorted chamber pieces with winds, piano and/or strings.

His works for winds also include his Symphony in B-flat written for the U.S. Army Band “Pershing’s Own”, in 1951. (Seeing as Pershing led the American forces when Hindemith was serving in the German Army suggests a bit of irony here. But Hindemith was definitely on he Allied side in World War II and afterwards.)

After the Roaring Twenties

For many, Hindemith was considered to be a more palatable modernist than Schoenberg and the other composers of the Second Viennese School. By the 1930s he had established himself as one of Germany’s preeminent musicians and composers, yet when the Nazi leadership seized power in January, 1933, much of his music was soon banned for “cultural Bolshevism” (one of those meaningless terms that Nazi censors used against artists). Although he tried to accommodate the new political leaders (he assumed they would be turned out of office shortly) and even enlisted conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler to champion his cause, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels branded Hindemith a “dud,” a “charlatan” and an “atonal noisemaker.” Hindemith’s support of Jewish composers and the fact that his wife had a Jewish grandfather didn’t endear him to the regime, either.

Unable to work in Germany, he was invited by the Turkish government to make several trips to Ankara to advise them on music education in Turkey. During three trips he also helped several Jewish musicians to escape Germany to Turkey. In 1939 the Hindemiths emigrated first to Switzerland and, in 1940, to the United States. He had invitations from several American universities and from Tanglewood to teach. After a series of lectures at Yale University, he was given a visiting professorship and later a permanent post. Reluctant to return to Germany after the war, he finally returned to Zurich, Switzerland, in 1953. From there he taught and traveled throughout Europe (as well as to South American and Japan) to conduct and record (especially his own works; with new stereo technology, everything needed to be re-recorded). Composing to the end, he died in Frankfurt from pancreatitis at age 68, but was buried in Switzerland, not Germany.

If Hindemith were alive today, he would be amazed by the number of student ensembles who have recorded movements of Kleine Kammermusik and posted them on YouTube. He would probably see it as an endorsement of his ideas on education and Gebrauchsmusik (music for use).

Scores and Recordings

You can download a copy of the score and parts of Kleine Kammermusik from the International Music Score Library Project. (Not allowed in Europe, but available elsewhere.)

See our listing for Paul Hindemith in Brandt’s Woodwind Quintet list.

There are many commercial recordings of Op. 24, No. 2 and it continues to be standard repertoire for woodwind quintets today. There are several performances available online, too, including:

A live and lively performance (which doesn’t name the ensemble) is performed by Wally Hase, flute and piccolo; Nick Deutsch, oboe; Thorsten Johanns, clarinet; Ole Kristian Dahl, bassoon; and Saar Berger, horn.

A very polished recording by members of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra is spread out over five files on YouTube: 1. Lustig. Mäßig schnell Viertel ; 2.Walzer: Durchwegsehr leise ; 3.Ruhig und einfach ; 4.Schnelle Viertel ; 5. Sehr lebhaft . Although not listed on YouTube, the performers are Paul Verhey on flute and piccolo; Jan Spronk, oboe; Piet Honingh, clarinet; Brian Pollard, bassoon; and Julia Studebaker on horn.

A historical recording by the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet made in 1956 by William Kincaid (flute & piccolo), Anthony Gigliotti (clarinet), John de Lancie (oboe), Sol Schoenbach (bassoon), and Mason Jones (french horn) is available. The version on YouTube includes some record noise. The ensemble may have set the world speed record for performing the fourth movement in 37 seconds. The entire performance clocks in at 12:05. (Perhaps they sped things up to squeeze this and four other quintets onto the LP.)

A live concert recording of the Tel Aviv Wind Quintet of 2013 is also featured on YouTube, with Roy Amotz, flute; Yigal Kaminka, oboe; Danny Erdman, clarinet; Nadav Cohen, bassoon; and Itamar Leshem, horn.

The French ensemble Quintette Moraguès made an excellent recording of the work and shares it in a set of five YouTube videos, beginning with the first movement (Lustig. Mäßig schnell Viertel). It’s followed by the second movement (Walzer); the third movement (Ruhig und enfach); the fourth movement (Schnelle Viertel); and the fifth movement (Sehr lebhaft). It’s worth wandering through the links, since it is, perhaps, the most polished performance in this list and my favorite interpretation. Performed by Michel Moraguès, flute & piccolo; David Walter, oboe; Pascal Moraguès, clarinet; Pierre Moraguès, horn; and Giorgio Mandolesi, bassoon. If you haven’t heard this ensemble before (I confess that I hadn’t), it’s a good introduction.

And, if you want to explore Hindemith’s Septet, there are several recordings available on YouTube worth exploring, both live performances and studio recordings.

Next: Next in our discussion of the Quintet in the Roaring 20s is Carl Nielsen’s Quintet, Op. 43, also composed in 1922.

Credits

Title photo of Hindemith with a viola is widely distributed on the web. I’ve been unable to find the original source, but it’s on almost every viola player’s website.

Photo of the Hindemith Family is from the Music4Viola website. Some restoration was done to adjust brightness levels for web display. Music4Viola also has a biography of Hindemith with some details not found in Grove’s or Wikipedia.

Photo of young Hindemith in uniform is from the website of the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen. It appears it is no longer available. Photo adjusted for web display in Photoshop.

Photo of Paul Hindemith in 1923 is from the Hindemith-Institut als Rechteinhaber unter GFDL zur Verfügung gestelltHochgeladen and the Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Paul Hindemith with a viola d’amore is from a Google Image search. It seems its original site is no longer in existence.

Caricature of Paul Hindemith is on a EMI Classics LP cover. Artist not listed online.

Score Art is by Andrew Brandt

Copyright © 2016-2024 by Andrew Brandt