Three Quintets You Probably Never Heard of

1923 – News Highlights

- Hitler’s putsch in Munich fails; he’s convicted and imprisoned for 8 months; writes Mein Kampf.

- To force Germany’s payments of war reparations, France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr region in January.

- The German mark continues to devalue to nothing: 4 billion marks = $1 US.

- Turkey declares independence.

- The burial chamber of Tutankhamun is opened and the sarcophagus is found. It captures the public imagination so much that “Old King Tut” by William Jerome and Harry Von Tilzer becomes one of the year’s hit songs.

- It becomes legal for women to wear trousers in the U.S.

- African-Americans Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, Joe “King” Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton and others make their first recordings.

- Time Magazine starts publication.

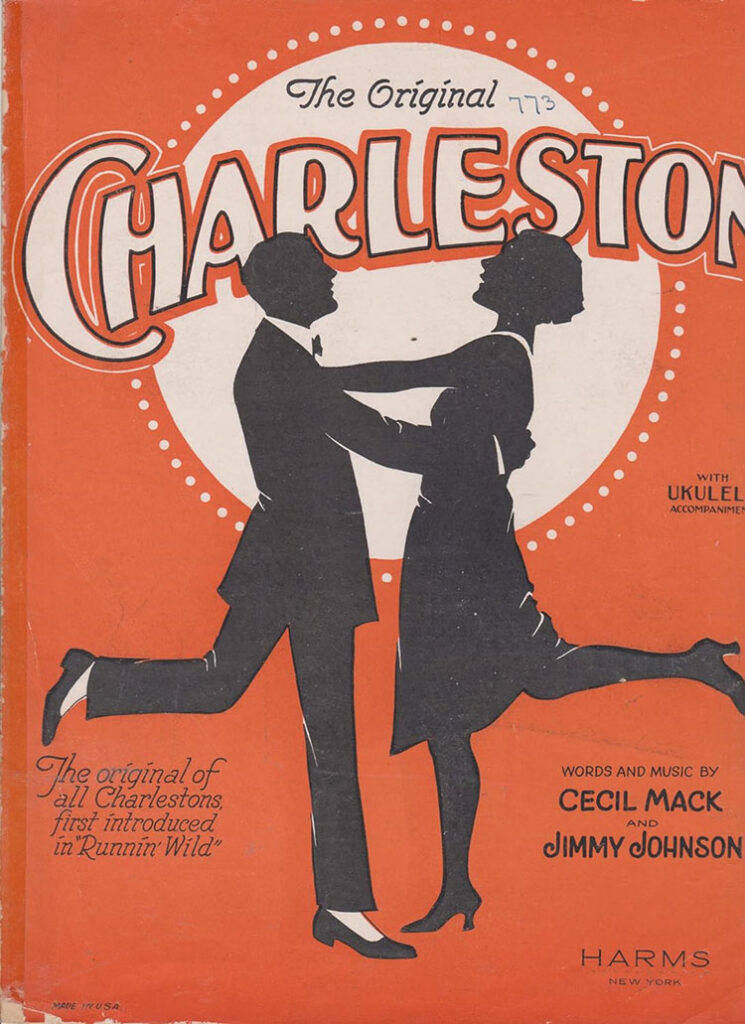

- Popular music: The “Charleston” by Cecil Mack & James P. Johnson is published, and becomes a wildly popular international dance craze that helps define the Roaring 20s. Frank Silver & Irving Cohn write “Yes! We Have No Bananas” and it becomes one of the year’s biggest hits. Also, “Barney Google (With the Goo- Goo- Googly Eyes)” by Billy Rose and Con Conrad is based on the popular cartoon character.

For 1923 we have works by Hanns Eisler, Carl Hillmann and Ludwig Weber.

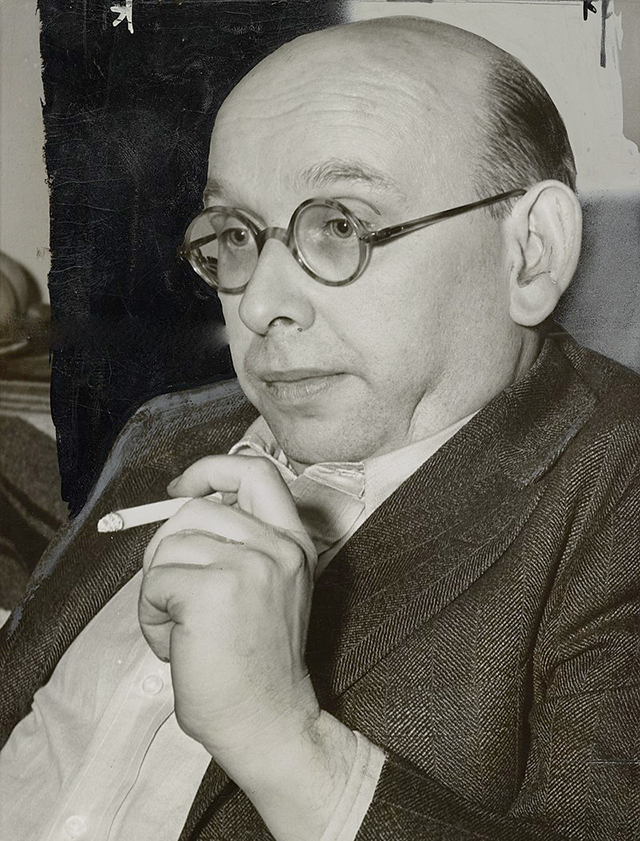

Eisler, Hanns [Johannes] (1898-1962)

Divertimento, Op. 4 (1923) was published in Wien (Vienna) by Universal Edition in 1977.

Although Arnold Schoenberg’s monumental Quintet of 1924 marks a landmark in his development of 12-tone music, it may surprise many that one of his students, Hanns Eisler, beat Schoenberg in finishing his own 12-tone quintet by a few months. (An excellent recording by Soni Ventorum is available on YouTube with the accompanying score in the video.) Although Eisler’s work appears to have many of the technical, rhythmic and ensemble challenges as Schoenberg’s Quintet, Eisler’s is only two movements (and about 33 minutes shorter) and sounds, to these ears, lighter in both its scoring and its overall aesthetic. Some of the variations in the second movement even made me chuckle. I consider this Divertimento to be one of the top finds in my latest research on 1920s quintets. This work would probably be more approachable to twenty-first century audiences than his teacher’s. (I would be wary about programming both quintets in one recital, but prove me wrong!)

Eisler studied with Schoenberg between 1919 and 1923 (with a brief break to study with Anton Webern) and wrote at least 3 works as a student. It is interesting that Eisler (the student) and Arnold Schoenberg (the teacher) were both writing a woodwind quintet at about the same time. (Schoenberg, however, had to stop composing for a while after the death of his wife.) Eisler and Schoenberg would soon have a falling out as Eisler turned to Marxist ideological and artistic principles politically, and to theater and film-score writing artistically.

Although Hanns Eisler never actually joined the Communist Party, his sister led the formation of the 1920s German Communist Party, owning the official party card No. 1. The Eislers and their colleagues actively campaigned against Hitler and the Nazis both politically and artistically. So, when Hitler rose to power Eisler had already fled Germany. He eventually ran short on safe havens in Europe and ended in the United States. He landed first in New York, where he taught film score writing at the New School while also actually writing film scores. He inevitably settled in Los Angeles, continuing his film-scoring career and reconnecting with his old German, Austrian and other European colleagues, including proffering a peace feeler to Arnold Schoenberg, already in Los Angeles. He even garnered a couple of Oscar nominations for his work.

But after World War II concluded, Eisler was brought before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and accused of being the “Karl Marx of music” and a Soviet agent. (His own sister, the actual card-carrying Communist, testified against him.)

He was deported in 1948 and forced to return to Europe, first to Vienna and later landing in East Berlin, where he continued to have a rocky relationship with the government. In his lifetime he was declared persona non grata first in Nazi Germany, then in the United States, and later in East Germany before being represented as a loyal German composer and teacher (not to mention composer of the East German national anthem), even as he kept his Austrian citizenship. The Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler in Berlin is named after him.

Other Hanns Eisler Works for Winds

Eisler also wrote a Nonet No. 1 for flute, clarinet, bassoon, horn, string quartet and double bass in 1939; a Septet No. 1 “Variations on American Children’s Songs” for flute (doubling piccolo), clarinet, bassoon and string quartet, originally written for the 1939 film “Kinderfilm”; and a Septet No. 2 for the same instrumentation. Like Schoenberg he only wrote the one woodwind quintet.

To Learn More

There is an in-depth biography of Eisler titled The Kaleidoscopic Contradictions of Hanns Eisler: 1898 – 1962 on the website Forbidden Music (the website about composers banned by the Nazi Regime).

The HANNSEISLERBLOG has a timeline of Eisler’s life on their website, plus an interesting bibliography.

The Music and the Holocaust website also has an article on Hanns Eisler.

Hillmann, Carl (1867-1930)

Hillmann’s Capriccio, Op. 56 was originally published by J. Andre, in Offenbach, Germany, ca. 1923. It was later published in New York by Boosey & Hawkes, and sold through Belwin, in 1940.

A German violinist and composer, he emigrated to the USA and, at age 26 (in 1893) joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra as Principal Second Violin in its third season and continued to perform with them until 1919. The online resources have little biographical detail about him and only one work, Legende, has a recording on YouTube. He was regularly published by André so one can assume that the actual composition of his quintet was not long before its publication in 1923. His composition style has been described as Romantic, but no description of Capriccio seems to exist online. This is one more quintet work that might be worth digging up from a library to play and record.

Weber, Ludwig (1891-1947)

Weber’s Bläserquintett (1923) was published by Moseler Verlag in Wolfenbuttel, Germany, in 1961.

Born in October 13, 1891 in Nuremberg, Ludwig Weber was a German composer and teacher (not to be confused with the Viennese-born bass singer, Ludwig Weber,1899-1979, nor with Ludwig Karl Weber, 1924-1988). The only biographical information I’ve found is in Grove Music Online, written by Klaus L. Neumann. Largely self-taught in music, he taught in primary schools in Nuremberg for some time. He became active in the German youth music movement (not to be confused with the later Hitler Youth Movement), joining the staff of the Essen Folkwangschule in 1927. A Ludwig Weber Society was created in 1949 to publish his manuscripts but, if it still exists, it has no online presence whatsoever. It’s possible that the Society did help get Weber’s Bläserquintett published by Moseler. According to WorldCat, there are several libraries in Europe and the United States (Harvard and University of Maryland) and 1 library in Australia (University of Sydney) which hold a copy of the work.

Credits

The photo of Hanns Eisler is dated 1940, which would make this from his American years. It seems every photo and caricature of Eisler includes him with a cigarette in hand. The source is Wikipedia.

Photo of Carl Hillmann is from the Musik un Musiker am Mittelrhein2 Online website. The only image of Carl Hillmann I could find online.

The cover for the sheet music of The Charleston (written in 1923) is in the public domain. There are many versions online.

Copyright © 2024 by Andrew Brandt