1928 News Highlights

- The major Western powers sign the Kellogg-Briand Pact (or Pact of Paris), renouncing the use of war to settle international disputes.

- Mickey Mouse makes his whistling debut in Steamboat Willie, the first popular sound cartoon. (Two previous Mickey Mouse cartoons were silent.)

- Alexander Fleming discovers penicillin.

- The first regular schedule of television programming begins in Schenectady, New York on W2XB. W2XBS soon becomes the first TV station in New York City. Unfortunately, few people would own TVs until after World War II.

- The first machine-sliced and wrapped loaf of bread is sold in Chillicothe, Missouri, using Otto Frederick Rohwedder’s technology. The machinery becomes so successful that every other popular invention since is called “The best thing since sliced bread.”

- The “iron lung” respirator is used for the first time at Children’s Hospital in Boston.

- Herbert Hoover is elected President.

- Eliot Ness begins leading the prohibition unit, The Untouchables, in Chicago.

- John James Audubon begins publication of The Birds of America in the United Kingdom.

- Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera) by Bertolt Brecht, Elisabeth Hauptmann and Kurt Weill premieres in Berlin. It includes the hit tune, “Mac the Knife.”

- Ravel’s Bolero premieres in Paris, he then embarks on a concert tour of the United States. Stravinsky’s ballet Le Baiser de la fée also premieres in Paris. Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra premieres in Berlin. George Gershwin’s An American in Paris is premiered by the New York Philharmonic.

- Popular Songs: “Basin Street Blues” by Spencer Williams; “Button Up Your Overcoat” by B.G. DeSylva, Lew Brown and Ray Henderson; “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby” by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh; “Let’s Do It, Let’s Fall in Love” by Cole Porter; “Makin’ Whoopee” by Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson; “Short’nin’ Bread” by Jacques Wolfe.

Heitor Villa-Lobos is one of the seven composers from our original series on Roaring 20s Quintets. The Quintette en forme de Choros was written in Paris in 1928. Our article on Villa-Lobos, the Brazilian Choro, and other wind works by Villa-Lobos has recently been updated and re-published.

The other composers we are discussing for 1928 are: Nicolai Berezowsky, Emil František Burian, Roberto Gerhard, Mary Howe, Karel Boleslav Jirák, Paul Juon, Edvard Moritz, Julius Röntgen, and František Suchý.

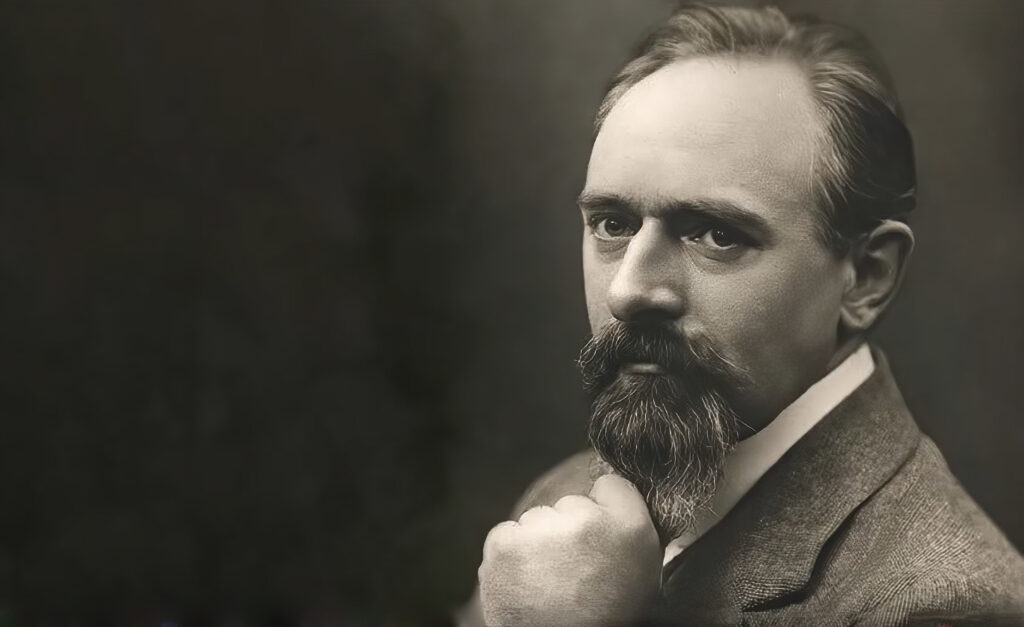

Nicolai Berezowsky

Suite No. 1, Op. 11 (1928). The original publication of Berezowsky’s Suite for woodwind quintet appears to be by the Russischer Musikverlag in Berlin in 1936. It was also available from Boosey & Hawkes in London, possibly at the same time. If you can’t find it for sale, there are many university libraries in the U.S. with a copy. Suite No. 1 was premiered by the Barrère Ensemble (likely in New York City and probably at Juilliard, where Berezowsky was studying at the time).

Nicolai Tikhonovich Berezowsky (also spelled Berezovsky) was born May 17, 1900, in Saint Petersburg in Imperial Russia; and died: August 27, 1953 in New York City. As a child, Berezowsky studied and sang with the chapel choir of the Imperial Capella, where he graduated with honors at 16. He later served as musical director of the School of Modern Art in Moscow and was first violinist of the Moscow Grand Opera. In 1922 he made a dangerous escape in disguise from the Soviet Union, only to be arrested in Poland, but released by an official who remembered hearing him playing violin. Berezowsky traveled to New York, continued his violin studies at the Juilliard School of Music, and performed with the New York Philharmonic for his first seven years in the U.S. He would have been a student at Juilliard when he composed his first woodwind quintet. The conductor Serge Koussevitzky would become a staunch supporter of Berezowsky.

A recording of the Suite No. 1 by The New Art Wind Quintet (recorded ca. 1950) is available on YouTube. The performers are Murray Panitz on flute; Melvin Kaplan, oboe; Aldo Simonelli, clarinet; Tina di Dario, bassoon; and Merrill Wilson on horn. The five movements are: 1. Allegro con spirito; 2. Adagio molto sostenuto; 3. Allegro giocoso; 4. Allegretto con melinconia; and 5. Allegro con brio. The scoring is for a normal quintet with the flute doubling on piccolo in the finale.

The Suite No. 1 is a quirky work, light-hearted on the surface, but with frequent dissonant harmonies (and polytonal bits) that suggest darker underlying currents. To these ears, the work sounds closer to members of Les Six with a dark Russian soul than to the Germans (Schoenberg and Hindemith) of the decade. But then the third movement adds some Hindemithian overtones. The slow second and fourth movements have a lonely dark-night-of-the-soul quality that adds depth to the work. The first and third and fifth movements have more energy and forward motion, but don’t reach an emotional resolution until the finale. When heard in context with more famous works of the 1920s, Berezowsky’s quintet at first hearing seems more frivolous and clown-like (especially in the first movement), but after a few hearings there’s a unique style under the surface that hints of a more serious, darker, perhaps Russian attitude to the music. In context of the aesthetics of the decade, this quintet holds its own against Hindemith, Schoenberg and the others. It deserves to be heard more often and also deserves a better recording.

Berezowsky also wrote a 16-minute Suite No. 2, Op. 22 for woodwind quintet in 1941. It was originally published in New York by Mills Music (now Belwin-Mills), and later published by EMI Music, Inc, and in Germany by Musikverlag Hans Gerig.

There are also problematic references online to a woodwind quintet of 1930 by Berezovsky, published by Moscow’s Muzyka press. But it seems extremely unlikely that Muzyka, the USSR’s official music press, would have published any music by Berezovsky in 1930 since he had defected from Russia and become a U.S. citizen by then. It’s more likely that someone confused the German Russischer Musikverlag with the Russian/Soviet Muzyka, and mis-dated the publishing year. The Musicalics online database also refers to a Quintet 2 of 1937, which is probably a badly-dated reference to the 1941 quintet.

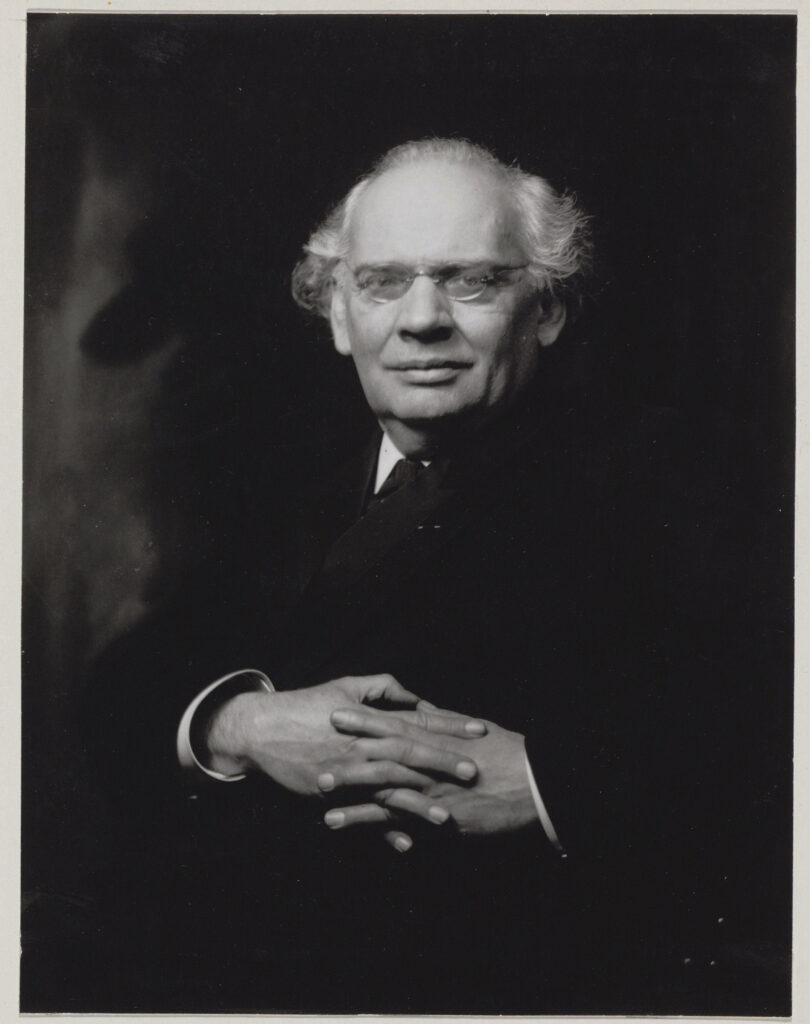

Emil František Burian

Emil František Burian (born June 11, 1904, in Pizeň (Pilsen) in the Czech region of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire; died August 9, 1959 in Prague) wrote two woodwind quintets during the 1920s that appear to have not been published: Variationen über ein Volkslied in 1928 and Vier Stücke für Bläserquintett in 1929.

Burian was a Czech composer, poet, journalist, singer, actor, composer, band leader, playwright and director. He was the son of a Czech operatic baritone (also named Emil Burian) and also nephew to Karel Burian, a tenor. Emil was active with Czech avant-garde theater artists in the 1920s while still a student. He graduated from the Prague Conservatory in 1927 where his composition teacher had been Josef Bohuslav Foerster (also a composer of a woodwind quintet of 1909).

Burian soon adopted a wide range of musical composition styles, influenced by jazz, Les Six, dadaism and later folk music and, after the war, social realism. He wrote a ballet Fagot a flétna (The Bassoon and the Flute) in 1925, which invites curiosity. A member of the Communist Party, the Nazis arrested him in 1941 and he was shipped to concentration camps in Theresienstadt, Dachau, and finally Neuengamme. In 1945, he finally returned home to Czechoslovakia to the surprise of family and friends who had presumed him dead! He also composed string quartets and operas and a jazz opera, but was also active in opera production, staging and singing.

Until a Czech musicologist can locate the two 1920s works, Burian also composed a Quintet (Kvintet pro flétnu, hoboj, klarinet, lesní roh a fagot) of 1933 that was published in Prague by Artia (or Národní hudební vydavatelství Orbis), consisting of 6 short pieces, and a Nonet (1938) for woodwind quintet and strings.

Roberto Gerhard

Gerhard’s Wind Quintet (1928) was published in London by Mills Music in 1960 and also by Boosey & Hawkes (possibly rental only). The work’s duration is about 15:30. The flutist doubles on piccolo.

Roberto Gerhard was born September 25, 1896 in Valls and died January 5, 1970 in Cambridge, United Kingdom. He was born in the Catalan region of Spain, to a Swiss-German father and a mother from Alsace, making Gerhard a Catalan, a Spaniard, and an internationalist. Although his musical education was interrupted by World War I, he studied briefly with Granados and others and grew interested in combining the most modern European composition techniques with the regional music and style of Iberian folk music, often using Bartók as a model. Traveling between Paris, Vienna and Berlin, Gerhard quickly adopted the styles of modernist composers and eventually settled in with the Second Viennese School, studying with Schoenberg from 1923 to 1928. After ending his studies with Schoenberg, he returned both to Barcelona and to his Catalan folkloric style. Nevertheless, he continued to bring modern European music to Spain, and hosted Schoenberg and his wife for 8 months, in 1931-32, where much of Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron was written.

During the Spanish Civil War, Gerhard was clearly on the Republican side, and music of this period was pro-Republican and pro-Catalan. He was in France when Barcelona fell to Franco’s forces, and thus exiled. With an invitation to teach for one year at King’s College in Cambridge, Gerhard ended up settling there for the rest of his life, hoping for the fall of Franco and the return of artistic freedom in Spain. Since British audiences were not terribly interested in 12-tone music and other modernisms, he spent much of the rest of his life back and forth: composing works with Spanish themes for the BBC radio, stage and screen, and continuing serial and, later, electronic musique concrète techniques in his serious “classical” works. And yet, Catalan folk elements continued on. Franco ended up dying the same year as Gerhard so the composer never returned to Spain. But, with the restoration of democracy, Gerhard’s music would finally be performed again in Spain, and late in the 20th century he was proclaimed as “Catalonia’s most important composer in four centuries.”

Gerhard’s quintet was written after studying with Schoenberg from 1923 to 1928. His Woodwind Quintet of 1928 uses neo-classic forms with serial techniques, here using a row of 7 notes with diatonic references more freely than Schoenberg did in his quintet. According to John France’s article from MusicWeb International, the work was premiered after Gerhard’s return to Barcelona on December 22, 1929 at the Palau de la Música Catalala. The performers were Esteve Gratacós on flute; Cassià Carles, oboe; Joan Vives, clarinet; Anton Goxens, bassoon; and Ramon Bonell on horn, all conducted by the composer. The work’s first printing was not until 1960, by Mills Music, Ltd.

Also according to John France, the first recording of the work was on a 1962 LP on the British Argo label by The London Wind Quintet, also with works by Mátyás Seiber, Peter Racine Fricker, and (of all things) Malcolm Arnold’s Three Shanties. (One cannot imagine a greater aesthetic gulf than that of the Gerhard and Arnold works.) The performers were Gareth Morris on flute; Sidney Sutcliffe, oboe; Bernard Walton, clarinet; Gwydion Brooke, bassoon; and Alan Civil on horn (this time without conductor). This recording and a live concert video by the Quintetto de Viento de la OCG are both available on YouTube.

Grove Music Online, alone, lists an earlier woodwind quintet by Gerhard of 1926, in two versions that were never published. He also wrote a Nonet (1956-7) for wind quintet, trumpet, trombone, tuba and accordion.

Mary (Carlisle) Howe

Mary Howe (who was referred to in social circles as Mrs. Walter Bruce Howe) was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in April 4, 1882, she trained as a pianist at the Peabody Conservatory and later, when she decided to devote more time to composing, she returned for a a 1922 diploma in composition after studying with Gustav Strube (who also wrote a woodwind quintet in 1930 which we will discuss later). Howe also studied in 1933 in Paris with Nadia Boulanger.

Her Suite for Wind Quintet (1928) is likely unpublished. Other than the fact that she wrote the piece it is difficult to find any information about the work or to locate the score. It is possibly part of the family’s private collection of music and memorabilia.

Mary Howe was a notable American pianist and composer who was also instrumental in creating the National Symphony Orchestra (of Washington, DC); worked with Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge to form the Chamber Music Society of Washington (later the Friends of Music of the Library of Congress), and organized, with Amy Beach, the Society of American Women Composers. So it is surprising how difficult it is to get good information about her and her music.

From a well-off family and married to a successful Washington attorney, Mary Howe was able to study, perform and compose without the urgency of the commercial aspects of making a living as a composer or as a teacher. As a result, many of her works were not published. She spent much of her effort, instead, on creating musical institutions and helping other women composers.

Howe’s 1957 Wind Quintet is the only one of her quintets mentioned in the list of archives in the New York Public Library’s papers of Mary Howe. Its creation also has a story. It seems that on the Vienna Philharmonic’s first tour of the U.S., they performed concerts in Washington’s Constitution Hall on November 4 and 5, 1956. Sometime, likely during their Washington stay, they read Howe’s orchestra suite, Stars, Sand and Rock. According to Diana Ambache, British pianist and historian on women composers, they enjoyed the work so much that the principal wind players requested that she write a woodwind quintet for them. The 1957 Wind Quintet is the result, so it is conceivable, if not likely, that the first performance of this work was in Vienna, Austria, not Washington, DC. But we don’t have documentation of that concert.

Ms. Ambache also gives her personal description of the music: “The music is expressive and wide ranging, and shows a fine ear for instrumental colours. The first movement plays wittily with rustic-sounding themes; the second makes eloquent use of the horn’s melodic powers; the third is a faintly ironic Viennese waltz; and although the finale begins with a solemn chant, it develops with jazzy syncopations and Yankee-flavoured folk tunes. … [See more on Diana Ambache’s website.]

Other woodwind quintets by Howe, besides the two listed above, include: Quintet for Four Woodwinds and French Horn (a manuscript was in the catalog of the Library of Congress); and Four Pieces for Wind Quintet. If anybody has any other information of Mary Howe’s quintets, please contact me.

Although there has been some good research on Mary Howe’s correspondence and her administrative and philanthropic work, there is a great lack of information about her chamber music, especially for winds – with ample material for a doctoral thesis here if one can dig up the music.

Karel Boleslav Jirák

Jirák’s Wind Quintet, Op. 34 (1928) was published in New York by Independent Music Publishers in 1961. Today, the only WorldCat-affiliated library known to have a copy of that New York publication is the music library of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Karel Boleslav Jirák (born on January 28, 1891 in Prague; and died January 30, 1972 in Chicago) started his career as chorus master at the Vinohrady Theatre in Prague. He was conscripted in 1914 to the army, but soon released after the discovery of a heart condition. Jirák later worked at the Hamburg Opera (1915-1918), then as director of the Brno and Moravská Ostrave opera houses (1918-1920, then as the conductor of the Prague choir Hlahol and second conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

When the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) was founded in 1923, Jirák was instrumental in developing and leading the Czech section and successfully pushed the ISCM to hold their International Music Festival in Prague in 1924 (in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of the birth of Bedřich Smetana).

During the 20s, Jirák taught composition at the Prague Conservatory and was principal conductor of the Czechoslovak Radio Orchestra until 1945, the end of World War II. His Wind Quintet, Op. 34, and his Second String Quartet (1926-27) won the Czech State Prize in 1928. The Wind Quintet was premiered on November 8, 1929, in Prague by the Prague Wind Quintet (Rudolf Hertl, flute; Václav Smetáček, oboe; Vladimír Říha, clarinet; Otakar Procházka, horn; and František Matějka, bassoon).

Jirák became one of the most popular Czech conductors in his country and in central Europe during the 1930s. During World War II, he composed and also conducted several patriotic Czech works, in particular, Smetana’s Má Vlast, which were hugely popular with Czech audiences (and much less so with the Nazis).

After the war, however, he was forced to withdraw from his posts for “asocial” and “non-Czech” behavior. Czechoslovakia had been independent and a democracy between the wars until 1938, when the country was split by the Munich Pact, then invaded by the Germans (in violation of the pact they had just signed). Both halves of the country became fascist until the Red Army liberated the country to make it Communist, creating three forms of Czech government in about ten years.

In 1947, Jirák accepted a well-timed invitation to teach music theory and composition at Roosevelt College in Chicago (from 1948 to 1967) and with the Conservatory college in Chicago. The Czech government, in the meantime, confiscated his property and the royalties from his compositions, recordings and from the sale of his books, and banned performances of his works. Because of this, he was granted permanent resident status in the United States, where he remained a Chicagoan for the rest of his life.

However, in 1968, the Central Committee of the Union of Czech Composers granted him honorary membership, briefly allowing Jirák’s works to be performed and paving the way for his return to Czechoslovakia, but the government appears to have reversed its decision after a short time. It wasn’t until well after his death that his urn was allowed to return to be placed in his family cemetery.

Jirák wrote a second woodwind quintet, titled Wind Quintet No. 3 (the second quintet being for strings). There is also a Serenade for Winds, Op. 47, written in 1944 and premiered February 15, 1945, in Prague by members of the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Alois Klíma. Also, in his Chicago years, he wrote a Trio, Op. 76, for oboe, clarinet and bassoon (1955-56) and several solo wind instruments with piano accompaniment: Sonata for clarinet Op. 59; Introduction and rondo for French horn Op. 68; Sonata for French horn, Op. 72; Sonata for oboe Op. 73; and a Sonata for bass clarinet Op. 92.

Another work for winds was his Symphonic scherzo for large wind orchestra, Op. 65A, written for the High School band in Cicero, Illinois, which was performed at the American Bandmasters Association convention in Columbus, Ohio. (He later created a version for orchestra which was premiered by Rafael Kubelik and the Chicago Symphony.)

Neither of his quintets appear to have been recorded and, with the exception of some of his solo sonatas, neither have his other wind compositions. Jirák’s music ranged a variety of styles and he was well acquainted with modern composition trends through most of the twentieth century. It would be wonderful if these works could be grasped from obscurity to be evaluated, performed and recorded.

Paul Juon

Quintett, Op. 84 (1928), published in Berlin by Richard Birnbach, 1930.

Paul Juon (originally Pavel Fedorovich Juon, and sometimes spelled Yuon) was born in Moscow in March 6,1872, to parents of Swiss and German background. He studied violin (with Jan Hřímaly) and composition (with Anton Arensky and Sergei Tanayev) in the Imperial Academy. He also studied flute for a while. A younger classmate, Sergei Rachmaninoff, dubbed Juon the “Russian Brahms.” Juon then went to Berlin to study at the Hochschule für Musik with Woldemar Bargiel, a colleague of (the original) Brahms and half-brother to Clara Schumann. Other than a short teaching stint at the Baku Conservatory in Azerbaijan, he appears to have spent most of his professional career in Germany, but due to illness he retired to Switzerland and died there on August 21, 1940.

A live recording of the Quintett (dating from around 1980, including the writer/editor of this website on bassoon) is currently available on YouTube.

Other works by Juon for winds include his Divertimento Op. 51 (1913) for woodwind quintet and piano, which received its New York premiere in a concert of the New York Chamber Music Society on November 12, 1918 in Aeolian Hall (in New York). There is also an Octet in B♭ Major (also listed as a Kammersinfonie), Op. 27 (1905) for oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello and piano. Score and parts for this work are available on the International Music Score Library Project.

As a postscript, Lisa Kozenko has written a dissertation about the New York Chamber Music Society, where she quotes several reviewers who found Juon’s work quite incomprehensible. One reviewer for the New York Sun wrote such an over-the-top vicious (and nonsensical) review at the premiere performance of his Trio Caprice, Op. 39 in 1909, that it was later enshrined in Nicolas Slonimsky’s entertaining book, the Lexicon of Musical Invective.

Moritz, Edvard

Quintett, Op. 41 (1928), was published in Frankfurt am Main by Wilhelm Zimmermann in 1928. This quintet is also included in the Andraud Collection, 22 Woodwind Quintets.

Edvard Moritz (whose name is occasionally spelled Edward or Eduard, and he occasionally used the pseudonym Herbert Loé), was born June 23, 1891, in Hamburg. He studied violin and piano and conducting before diving into composing. He then studied with Claude Debussy (although one biography says he didn’t study composition with him, which seems odd). He also studied piano with Ferruccio Busoni and composition with Paul Juon (yes, the one listed just above), and conducting with Arthur Nikisch. Moritz centered himself in Berlin and toured as a violinist and as a conductor to England, France, Spain, Portugal and Italy. His first composition performed by the Berlin Philharmonic was his Burlesque.

Moritz was persecuted by the National Socialists after they came to power in Berlin for being Jewish. From 1934 to 1935 he conducted a newly formed Jewish chamber orchestra, which included several well-known Jewish professional musicians in Hamburg, in retrospect a dangerous protest. He also became conductor of the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Berlin in 1936 to 1937. Eventually, the Nazi government banned him from performing. In 1937, Moritz obtained a visa to travel to the United States and traveled to New York on the S. S. Königstein. He established a chamber orchestra which performed in Town Hall and became a teacher of piano and composition. He was naturalized in 1943 and appears to have remained in the United States until his death on September 30, 1974.

Quintet, Op. 41

- Allegro ma non troppo

- Scherzo. Vivace (Sehr lebhaft)

- Andante (Ruhig)

- Sehr lebhaft (Molto vivace. Sempre alla breve)

Moritz’s Quintett, Op. 41 was composed in 1928, likely in Berlin, and dedicated to Dem Hamburger Bläser-Quintett. Otherwise we know nothing about the circumstances of the composition or the performance. The original publisher was Wilhelm Zimmerman, in Frankfurt am Main. It was later published as part of Andraud’s Twenty-Two Quintets, which is still in print (and recently re-edited). The score and parts are also available for download in those countries where the copyright has expired from the International Music Score Library Project.

Surprisingly, I could find no professional recording of this quintet listed in WorldCat or via Google or on YouTube. The quintet, compositionally, definitely looks back towards a Romantic style, rather than the most forward looking works of the 1920s. But a good interpretation would definitely be worthwhile listening.

Moritz’s other works for winds include a second woodwind quintet, Op. 169 composed in 1963 (in America) and published in 1968 by Musikverlag Zimmermann (also available from Theodore Presser and other vendors). There is also a Divertimento, Op. 150, for flute, clarinet and bassoon. For larger ensembles there is a Concerto, Op. 55 (1927) for wind orchestra and a Divertimento for wind orchestra and harp. Wikipedia (Dutch and French-language) lists a mysterious third woodwind quintet of 1968 without opus number, but this is probably a confusion with the Op. 169 quintet published in 1968.

Julius Röntgen

Julius Röntgen was already retired when he wrote two short works for woodwind quintet in 1928. One was his Serenade of 1928 for woodwind quintet (this was his second serenade for winds, the first being his 1876 Serenade for wind septet). The 5-movement 1928 Serenade was published by Edition Compusic in Amsterdam in 1988. It was also published in 2011 by the tiny publishing house in Manhattan, Kansas, Prairie Dawg Press in 2011, run by Bruce Gbur (who passed away recently). Both Serenades were more recently recorded by the Linos Ensemble in Germany in 2012.

Also in 1928, Röntgen completed his Scherzo for woodwind quintet, also published by Prairie Dawg Press. This work includes a contrapuntal display of excerpts from the U.S. National Anthem. Both of these works were reportedly dedicated to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (in Washington, DC), but none of the material I’ve seen explains why.

Julius Röntgen was born in Leipzig on May 9, 1855. His father, Johann Matthias Engelbert Röntgen, was a violinist in the Gewandhaus orchestra and his mother was an excellent pianist. Growing up in Leipzig, young Julius started composing at the age of nine and made his compositional debut (at about age 14) in Düsseldorf with a duo for two violins, which he performed with his father. He studied composition with Friedrich Lachner (then director of the Gewandhaus orchestra) and studied piano with Carl Reinecke, among others. His early compositions were also influenced by Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms. He became friends with Grieg and Brahms and had met Liszt in person. In 1884, when Röntgen soloed in Brahms’s second piano concerto in Amsterdam, Brahms conducted. Grieg dedicated his Lyrische Stücke, Op. 54, to him.

After graduation, Röntgen moved to Amsterdam to teach and spent most of the rest of his life in The Netherlands. He was one of the founders of the Amsterdam Conservatory in 1884 and became its managing director from 1913 to 1924. Röntgen was, obviously, too old to serve during World War I, but one of his sons was taken prisoner by the Germans, while another emigrated to the United States and served in the U.S. Army. After the war Röntgen was banished from Germany and he took Dutch citizenship. In 1924 he retired from the Amsterdam musical world and moved to rural Bilthoven where one of his sons, Frantz, built him a house they named Gaudeamus. In his last eight years, he wrote more than 100 of his 610 works. Most of his compositions were not published, but many of them now are in archives of the Nederlands Muziek Instituut in The Hague.

Naturally, most of his works were written in the Romantic era, but he was aware of trends in the 1920s and studied the music of Hindemith, Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Pijper. He experimented with atonal music and his 1930 symphony was bitonal.

There were other works for winds, too. He wrote his Serenade, Op. 14 (1876) for flute, oboe, clarinet, 2 bassoons and 2 horns. He also wrote a Quintet in G Major in 1911 for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and piano. Smaller works include two Sonatas for oboe and piano (the second one also composed in 1928), plus a Hirtenlied for oboe and piano. He also wrote a Sonata for bassoon and piano in 1929.

He died at age 77, on September 13, 1932 in Utrecht, in The Netherlands. The Dutch Music Institute maintains a website dedicated to Julius Röntgen in both Dutch and English.

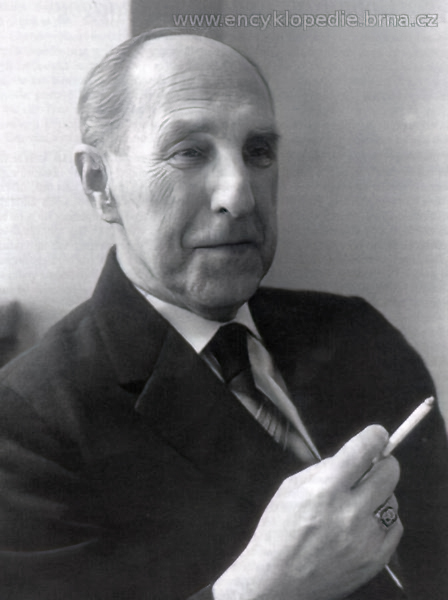

František Suchý, Brnensky (of Brno)

Bläserquintett, Op. 5 (1928) was the first of several quintets by Suchý. Although they are listed in various Czech sources, no publication information is given for most of them. As founder, leader and oboist of the Moravian Wind Quintet, they were likely all written and performed for their own ensemble.

František Suchý was born on April 9, 1902 in Libina, a village which dates back to 1358, in the district of Šumperka in the Olomouc region in what is now the Czech Republic. He studied oboe with Matěj Wagner and composition with Jaroslav Kvapil at the Conservatory in Brno and continued his composition studies with Vítězslav Novák in Prague.

From 1927 to 1947, he was principal oboe of the Brno Radio Orchestra. Afterwards he was oboe professor at the Brno Conservatory, and from 1949 he also lectured at the Janáček Academy of Performing Arts in Brno. He founded and led the Moravian Wind Quintet sometime before 1930. He also served as chairman of the Brno branch of the Association of Czechoslovak Composers.

There was another Czech composer using the name František Suchý (1891-1973) who was a conductor and composer based in Prague. Today most reference works describe him as František Suchý Prazsky (of Prague), whereas the composer we are concerned with here is František Suchý Brnensky (of Brno).

Other František Suchý works of interest to quintet players include:

- Serenada, Op. 30 for woodwind quintet

- Quintetto Concertante (Koncertantni kvintet), Op. 34 (1947), published in Prague by Panton in 1969. Listings are inconsistent, but this appears to be a work for woodwind quintet and orchestra.

- Quintetto Concertante (Koncertantni kvintet), Op. 34A (1947) appears to be a version of the same work for woodwind quintet alone.

- Three Czech Dances, Op. 40 (1952) for woodwind quintet

- Bläserquintett, Op. 45 (1958)

- Concertino, Op. 13 (1931) for woodwind quintet and violin

- Nonet, Op. 46 for woodwind quintet and violin, viola, cello and double bass

- Wind Sextet, Op. 48 (1960) but the exact instrumentation is not given.

With such a rich resource of Czech wind writing, it’s a shame most of these works have no publisher or other information on how to find them. We need a Czech-speaking musicologist to track these compositions down, make a performance edition, and then some recordings.

Credits

The image of Nicolai Berezowsky is from the website, Prone to Violins, but is widely distributed through the web.

The image of Emil Frantisek Burian is from Czech Radio.

The image of Roberto Gerhard is widely distributed on the Internet, including on the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona Department of Art and Musicology website.

Mary Howe’s photo comes from the Art Song Augmented website, which includes a short biography of Howe, several videos of her songs, and links to other writings about Howe.

The photo of Karel Boleslav Jirák is from Wikipedia. It was edited for noise removal.

The image of Paul Juon is a screen grab from a YouTube video of Juon’s Trio-Miniaturen for piano trio. Other cropped versions of the original image are scattered across the internet.

Image of Edvard Moritz is from Wikimedia and in the public domain. Is was enlarged and de-noised in Photoshop and Topaz Lab’s Denoise AI and adjusted for web display.

The image of Frantisek Suchy (the only image of him I found on the web) is from the Encyklopedie Brna.

The cover image of Eliot Ness is in the Public Domain and downloaded from The Wikimedia archives: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=430158

Copyright © 2024 by Andrew Brandt