Early Twentieth Century Reed Trios

As we mentioned at the end of our previous article, there was a break of almost 25 years between the time of the compositions of reed trios by Huguenin and Flegier and the next known compositions for oboe, clarinet and bassoon.

Gabriel Allier’s Scène Champêtre

The first trio d’anche written in the twentieth century could be attributed to Gabriel Allier (born September 6, 1863 in Lyon, France, and died in Paris on January 31, 1924). The work is Scène Champêtre [Country Scene], written in 1920, and is scored for oboe (or flute), clarinet, and bassoon (or horn). It was published in Paris by Margueritat, circa 1920. But the score itself is where the attribution is tricky.

The work was likely intended for younger or amateur ensembles. The cover description of the trio’s performance options gives so many substitutions for other instruments that it seems like almost anything except a trio d’anche. But a look at the actual score confirms that the primary orchestration is for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, but even here we see the option to use flute instead of oboe and the package includes an alternate horn part to be used in lieu of a bassoon. After all that, the score shows the piece to be light, simple, and short. The bassoon part is so simple (the first 34 bars only use the pitches of G and D, with a single A for variety) that the bassoonist would probably be happy to offer a hornist their chance at the work.

A new, modern edition of this trio by TrevCo Music Publishing in Florida offers the instrumentation of oboe, clarinet and bassoon, but he also publishes alternate editions for oboe, English horn, and bassoon; and for 2 oboes and English horn. The trio was originally published in Paris by Margueritat, ca. 1920. It is this edition that is available for download from the International Music Score Library Project.

Gabriel Allier was primarily a military band conductor, and his Scène Champêtre was one of his first compositions written after he retired from the French army in 1918, at age 55. Most of his compositions were either for band or piano, so even for him, this work was a curiosity.

However, if Allier’s work seems a bit iffy as a genuine trio d’anche, there is no question that the first famous twentieth century work for oboe, clarinet and bassoon was not by a Frenchman, or a German, or a Swiss composer, but by a Brazilian!

The First Brazilian Reed Trio – by Villa-Lobos

Heitor Villa-Lobos was born March 5, 1887 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and died there on November 17, 1959. In addition to being Brazil’s most famous composer (writing over 2000 works), he was also active as an educator and conductor.

In 1921, Villa-Lobos wrote his Trio for oboe, clarinet and bassoon in Rio de Janeiro. When he traveled to Paris for the first time in 1923, he brought the score with him and the Trio was premiered in Paris on April 9, 1924 by the French trio of Louis Gaudard, oboe; Gaston Hamelin, clarinet; and Gustave Dherin, bassoon. They performed the work as part of a Jean Wiéner concert series in the Salle des Agriculteurs in Paris. [See Catherine McGee Stockwell, in “The Oiseau-Lyre Wind Trios” p. 4.]

The work was later published in 1928 in Paris by Max Eschig, where it is still available. There was also an edition published in New York in 1985 by International Music. The score is available for free download in those countries where the copyright has expired from the International Music Score Library Project, https://imslp.org/ .

The Trio is in three movements: Animé; Languissamment; and Vif. The work lasts about 18 minutes and 40 seconds. There are several recordings immediately available on YouTube.

In 1924, this work was cutting-edge modern and had its detractors, including French composer and critic Georges Auric who described the trio as “grimacing… a painful mixture of clichés of ‘modernism.’” [Quoted (and translated?) by Catherine McGee Stockwell in “The Oiseau-Lyre Wind Trios”] It’s hard, today, to imagine how a highly original work by a Brazilian composer of Villa-Lobos’s stature could possibly be called “clichéd” or “grimacing” in the Paris of 1924. In any case, Auric would later write his own trio d’anche in 1938 in a decidedly non-grimacing style.

Today, Villa-Lobos’s Trio remains one of the more rewarding works for the trio d’anche, while both this work and Auric’s are still performed, this is the more adventurous, exotic, and challenging.

See our article on Heitor Villa-Lobos and his woodwind quintet for much more info about the composer and his works for winds.

Another French Reed Trio, Maybe – Charles Koechlin’s Trio

Charles Koechlin’s Trio, Op. 92, written in 1924, is scored for flute (or oboe), clarinet and bassoon (and so you see the problem of calling this a reed trio). It was published in 1928 in Paris by Maurice Senart. (It also may be performed by violin, viola and cello.)

This Trio is another iffy work for the purposes of this list. Although it is easily performed as a trio d’anche, the original score shows it to originally have been for flute, clarinet and bassoon, part of the many works where the top part might be performed by either a flute or by oboe. A native Parisian, Charles-Louis-Eugène Koechlin was born there on November 27, 1867 and died in Le Canadel in the Var region (on the coast of the Mediterranean) on December 31, 1950.

Even if you don’t count this trio as a “real” trio d’anche, Koechlin’s redemption comes with his 1945-composed Trio d’Anches, Op. 206, now definitely for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, first published in Paris by Nouvelles Éditions Méridian in 1957. This later trio was first performed on French National Radio on March 5, 1946 by Trio Dupont: oboist Paul Taillefer, clarinetist André Dupont, and bassoonist André Gaby. But, we digress.

The First Russian Reed Trio – by Dmitry Milkikh

Dmitry Mikheyevich Milkikh (there are many spelling variations on this name, including Melkich, Dmitry, Dmitriĭ, Dimitrij, Mikheevich and more) was born in Moscow on January 31 or February 12, 1885 – depending if you use the old Russian Julian calendar or the Gregorian calendar. His death was (Gregorian style) on February 22, 1943, also in Moscow.

Coming of age in a tumultuous period of Russian history, Melkikh received a law degree from Moscow University and studied music at the newly-opened People’s Conservatory as he was able. He was in and out of the military, including during the Russian Revolution (the biography by Inna Barsova in Grove Music Online doesn’t make entirely clear which side he was fighting on, but it appears to have been the White Army (eventually the losing side). After the revolution, he composed and taught briefly at the Moscow Conservatory. In 1924 he became a member of the Association of Contemporary Music. Much of his music is described as being of an older, Romantic style.

The Trio, Op. 17 (November, 1926) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon was published simultaneously by Muzsektor Gosizdata in Moscow and by Universal Edition in Vienna in 1928. The Trio’s score and parts are available for download from the International Music Score Library Project. The work is fairly substantial, with a duration of 13 minutes. The movements are: 1. Molto cantabile; 2. Vivace scherzando; and 3. Allegro. It was composed in November of 1926. A modern recording was released in 2001 by Mary Ashley Barret, oboe; Kelly Burke, clarinet; and Michael Burns, bassoon on the Centaur label, CRC 2562.

Clearly not in the French style popularized later by the Trio d’Anches de Paris, this work might make a good contrasting style for a concert. A new performance and perhaps a recording might be a worthwhile project.

Milkikh also wrote a Quartet (1929) for flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon, Op. 19, published in Moscow by Muzsektor Gosizdata, which can also be downloaded from the International Music Score Library Project. He also wrote a Malen’kaya Syuita [Little Suite], Op. 24 (1936) for flute, oboe, clarinet and piano, but this may still be unpublished.

The First Austrian Reed Trio – by Paul Pisk

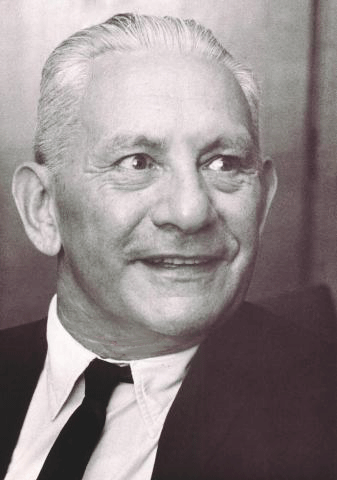

Paul Amadeus Pisk was born in Vienna on May 16, 1893 and died in Los Angeles in California on January 12, 1990. His father, Ludwig Pisk, was a secular Jewish lawyer and his mother, Eugenie Pollack, a Protestant. Paul Pisk received a doctorate in musicology from the University of Vienna. Both Paul and his brother Otto served in the Habsburg Army in World War I, Paul being a supply sergeant for the cavalry. He also received a diploma in conducting in 1919 from the Vienna Conservatory, and studied composition with Arnold Schoenberg.

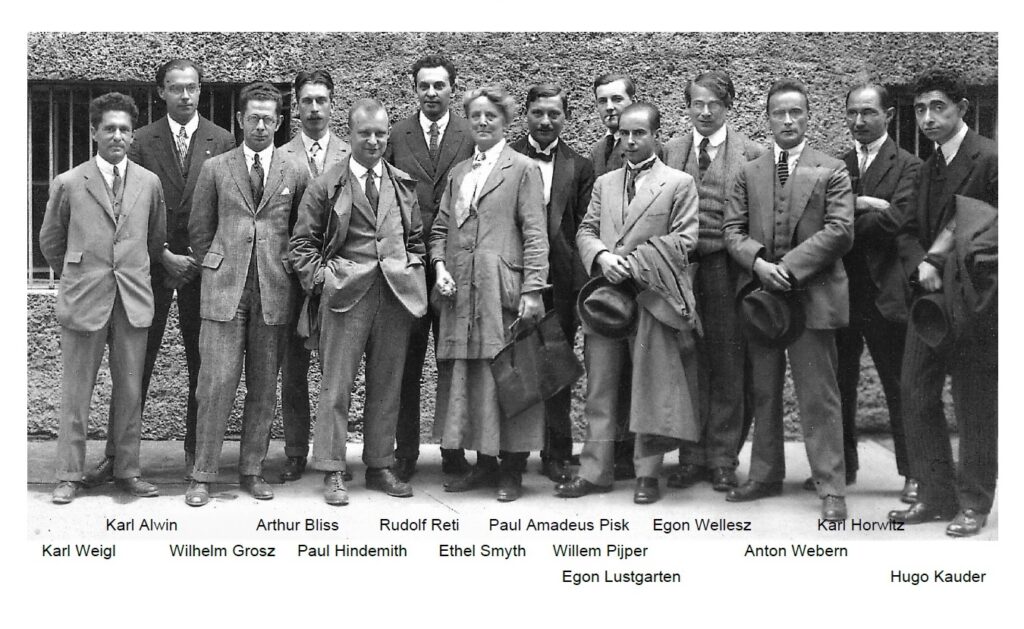

Pisk joined Alban Berg and Paul Stefan to jointly edit the Musikblätter des Anbruch from 1920 to 1928, and was a founding member of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) in 1922 and secretary of its Austrian branch. He directed the music department of the Volkshochschule in Vienna from 1922 to 1934 and also taught at the New Vienna Conservatory and the Austro-American Conservatory near Salzburg.

It was during this period, in 1926, that he wrote his Trio No. 1, Op. 18 for oboe, clarinet and bassoon.

With his international connections with the ISCM, he visited New York in the early ’30s to play Austrian music on CBS and attend live performances of his music. With the rise of the NAZI party in Austria, he emigrated to the United States in 1936, renewing his contacts with Schoenberg, Darius Milhaud and Paul Hindemith, among others. Soon he was teaching at the University of the Redlands in California and later with the University of Texas in Austin and Washington University in St. Louis. He became an American citizen in 1941.

Avoiding the 12-tone style of his teacher, Schoenberg, Grove’s notes that Pisk developed his own system of composition and use of dissonance in his works. I’ve not found recordings of any of his wind chamber music. If there is a professional woodwind quintet or trio d’anche ensemble wanting to explore a historical figure whose music is virtually unknown today, this could be a seriously useful recording project.

The other chamber works that Pisk wrote for winds date from his American years, during and after World War II:

- Little Woodwind Music, Op. 53a (1943) for oboe, 2 clarinets and bassoon

- Suite, Op. 85 for oboe, clarinet and piano (1954–5), published by the American Composers Alliance in New York

- Woodwind Quintet, Op. 96 (1958), published by the American Composers Alliance

- Trio No. 2, Op. 100 (1960) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, published by the American Composers Alliance

- Envoi, Op.104 (1964) for oboe, clarinet, bassoon and string trio, published by the American Composers Alliance.

- Discussions, Op.116 (1974) for oboe, clarinet, bassoon, viola and cello

- Elegy & Scherzino, Op. 70, No. 2 (1950) for oboe, 2 clarinets and bassoon

- Music for Violin, Clarinet, Cello and Bassoon (1962) published by the American Composers Alliance

- Plus works for flute, clarinet, and other combinations with piano.

In addition to his chamber music for winds, Pisk was internationally known for compositions which ranged from operas, orchestral, ballet, folk dances, and works for piano and chorus.

For more info on Paul Pisk, there is a short biography on the American Composers Alliance website. For an extended list of his works, see also a page by Elliott Antokoletz.

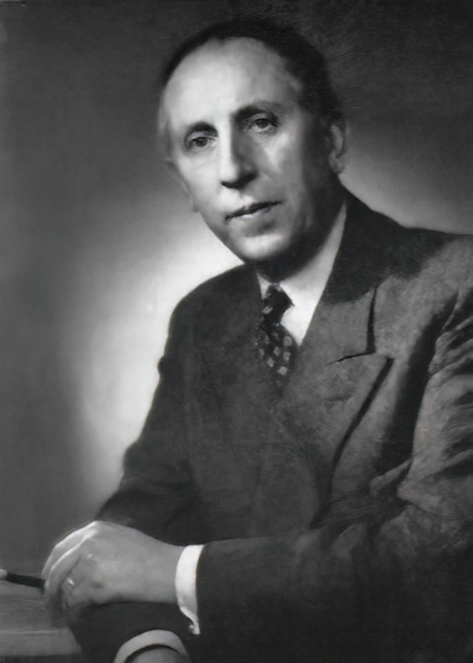

The First Swedish Reed Trio – by Hilding Rosenberg

Hilding C. Rosenberg was born on June 21, 1892 in Bosjökloster, Sweden; died May 19, 1985 in Bromma in Stockhom, Sweden. He wrote his Trio, Op. 42 in 1927, for oboe, clarinet and bassoon. I have not been able to find a publisher nor a recording of the work. Finding the score, performing the work and recording it might be an excellent project for a Scandinavian trio d’anche ensemble.

Hilding C. Rosenberg Biography

Rosenberg began his studies at the Stockholm Conservatory in 1915 and later became known as a pianist, organist, teacher and composer. After World War I he became a prominent conductor in Europe. He received a scholarship in 1920 which allowed him to study in Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and Paris, including developing contacts with Arnold Schoenberg and Paul Hindemith.

Although Rosenberg’s early works were first modeled after Sibelius, he eventually led the way for Swedish composers to move away from the late Romantic style. Most of his compositions were for orchestra, but his Trio, Op. 42 (1927) and his Wind Quintet (1959/1968 published by Edition Suecia) appear to be his only chamber music for winds alone.

Rosenberg was vice-president of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music from 1951 to 1953. He received an honorary doctorate from Uppsala University and was an honorary member of the International Society for Contemporary Music. So far I’ve found no recordings of his Trio. The Amade Woodwind Quintet has recorded the quintet (not the trio) and it is available on YouTube in separate movements.

He did write a Symphony for Winds and Percussion in 1966. A recording by the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra (conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen) on YouTube shows that Rosenberg has a mastery of colorful wind orchestration. Other works that feature wind soloists include a Romance for Clarinet and Orchestra, and a Sinfonia Concertante for oboe, bassoon, violin and viola and orchestra and a trumpet concerto.

The First Czech Reed Trio – By Erwin Schulhoff

The first Czech reed trio was written by Erwin Schulhoff. It was his Divertissement (1927), Trio for oboe, clarinet and bassoon written in 1927. The trio was published in Mainz by Schott, also in 1927. It can also be found on the International Music Score Library Project for download in those countries where the copyright has expired.

The trio has seven movements:

- I. Ouverture: Allegro con moto

- II. Burlesca: Allegro molto

- III. Romanzero: Andantino

- IV. Charleston: Allegro

- V. Tema con variazioni e fugato: Andante

- VI. Florida: Allegretto

- VII. Rondino-Finale

The trio was premiered in Paris on March 27, 1927 at a concert of the Société modern des instruments à vent. The Divertissement is about fifteen minutes long with some dazzling displays of technique by the players. Schulhoff seems to take the title literally, with each movement containing its own diverting quality. By this time, Schulhoff’s early fascination with the nineteenth century is long gone, replaced with light, often acerbic melodies and some dissonances that, today, shock much less than they probably did a hundred years ago. In many ways, when it imitates different styles of popular music, it presages some of the light, entertaining works that became staples for the Trio d’Anches de Paris.

There is the occasional multi-tonal effect and occasional chaotic exchanges between the players, but they all resolve into good-natured humor in a style to please both modern audiences and performers. The work doesn’t have the serious mien of several other works mentioned in this series, but is entertaining enough to become standard repertoire for modern trio d’anche ensembles.

There are several professional recordings of this work and others on YouTube. Most involve having to hunt down individual movements from YouTube search results. One performance in a single file (possibly by the Ensemble Villa Musica) is available, also on YouTube.

Erwin Schulhoff’s Life

Erwin Schulhoff was born in Prague on June 8, 1894. Erwin’s father, Gustav Schulhoff was a wool and cotton merchant and a part of a German family of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. His mother Louisa (née Wolff) was from Frankfurt where her father lead a theater orchestra. Erwin’s great uncle Julius Erwin was a piano virtuoso and composer.

Learning piano, Erwin was a prodigy, and by 1901 no less an authority than Antonín Dvořák recommended to his parents that he be trained for a musical career. By the age of 10 he was studying piano at the Prague Conservatory and he had a wide variety of distinguished teachers in schools such as the Horaksche Klavierschule in Vienna, the Leipzig Conservatory, the Cologne conservatory to study piano and composition. His composition models were equally diverse, starting with Schumann, Brahms and Dvorak, then Grieg and Richard Strauss, to Debussy, Reger and Scriabin.

But when World War I broke out, he was drafted into the Austrian army, where he spent four full years – years which broke down all the values he previously held, and he turned into a socialist. Musically, he soon edged towards atonality and Expressionism, while also playing with Dadaism from time to time and later jazz and quarter-tone music. Meanwhile, his concert and chamber music performances brought him around Europe and getting to know many of the leading musicians around Europe.

In the 1930s, however, his musical style became more conservative while his politics became more radical, moving towards Stalinist socialist realism. But under the rise of Nazism, he was attacked for his politics, his music, and his Jewishness. His music was labeled “degenerate” and he was blacklisted by the Nazi regime. He couldn’t perform and his music couldn’t be played. He attempted to emigrate first to the west and then the Soviet Union. After the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939 he could only perform under an alias. By the time the Soviet Union approved his petition for citizenship, he was already imprisoned by the Germans. In June, 1941, Schulhoff was sent to the Wülzburg concentration camp near Weissenburg, Bavaria, where he died from tuberculosis on August 18, 1942.

After the war, Schulhoff’s music had disappeared into obscurity until people began finding scores to print or reprint and his music became more popular beginning in the 1990s. Today there are several good performances of the entire suite on YouTube and on commercial recordings.

The First Belgian Reed Trio – by Karel Albert

The Belgian composer, Karel Albert, was born in Antwerp, on April 16, 1901; and died in Liedekerke on May 23, 1987. He attended the Antwerp Conservatory and later studied composition with Marinus de Jong. After World War I, Albert (often writing under the alias, “K. Victors”) joined with composers August L. Baeyens and Willem Pelemans to promote modern music in recitals, concerts and theater works. He was musical adviser and conductor of a traveling Flemish theater company named Het Vlaams Volkstoneel and later was an assistant director of the Flemish section of the Belgian National Broadcasting Service (NIR) until 1961 (with an interruption during World War II). He later concentrated on writing music reviews and composition, including music for the stage. Style-wise, his early works concentrated on Expressionism (which he called Constructivist), which gradually switched to neo-classicism, and he later experimented with atonal and serial music.

Albert’s Trio voor hobo, klarinet en fagot was written in 1930 and was premiered in Antwerp by the Trio van het Kamermuziekgezelschap van Antwerpen [Trio of the Chamber Music Society of Antwerp] in the same year.

Other works for winds by Karel Albert include a Kwintet (1954) for woodwinds and strings (flute, oboe, violin, viola and cello), published in Bruxelles by Le Centre Belge de Documentation Musicale. The second movement of the quintet is an exploration of the 12-tone system. He wrote a Werkstuk voor altviool en blazerskwintet [Workpiece for Viola and Wind Quintet] in 1958. He also wrote a Serenade for oboe and piano in 1921.

Another Russian Reed Trio – by Mikhail Ivanov-Ippolitov

Mikhail Mikhaylovich Ivanov was born in Gatchina, near St. Petersburg on November 7/19 [Julian Calender/Gregorian Calendar), 1859 and died in Moscow on January 28, 1935. As he began his career, he added his mother’s maiden name Ippolitov to distinguish himself from a composer and critic with an identical name (Mikhail Ivanov – 1849-1927).

Mikhail was taught music at home and as a choirboy of St. Isaac Cathedral, from 1872 to 1875. In 1875 he entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory as a string bass student. He studied canon and fugue from August Iogansen (Johansson) and studied composition with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov from about 1879 to 1882. He also joined meetings of the Balakirev circle. In 1882 he was appointed director of the academy of music in Tbilisi (Tiflis), Georgia, as well as conducting the local opera company, where he began a lifelong interest in Georgian music and, later, Uzbek, Kazakh, Turkmen, Turkish and Arabic music.

In 1893 he began teaching harmony, orchestration and composition at the Moscow Conservatory, where he remained the rest of his life (directing it from 1905 and 1922). He also continued as a conductor with the Russian Choral Society, Mamontov Opera, Aimin Opera and the Bolshoi Opera. He premiered operas by Rimsky-Korsakov, revived Mussorksky’s Boris Godunov at the Bolshoi as well as composing and conducting his own works.

As a composer, he was not one to adapt to the new styles of schools of composition of western Europe, sticking to his 19th century Russian roots. Where he was innovative was in adapting folk music of Georgia (such as in the Caucasian Sketches) and other southern Asian cultures.

Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov wrote his 2 Kirghiz Songs (1931) for oboe, clarinet, bassoon and piano ad lib. It was published in Moscow by Muzgiz, in 1931 (with piano score). Mercury Music in the U.S. also published it, ca. 1945. The trio is available for free download in those countries where the copyright has expired from the International Music Score Library Project.

The International Music Score Library Project, has three scores and a later set of parts for Ippolitov-Ivanov’s only trio for winds. The original scores, one with piano and one without, were printed by the Russian printer, Muzgiz, in 1931, in cooperation with the Viennese Universal publishing company, which distributed it through western Europe and New York.

The trio’s duration is a short three minutes. The two movements are Seineb; and Moldibaj. The 2 movements are based on tunes by the Kirghiz, a Turkic people who lived between the Volga and Irtisch Rivers in Asian Russia. The piano part exactly duplicates the three wind parts and could well have been an aid for teaching young students the work (or perhaps to fill in if all three players were not available). In any case, there doesn’t seem to be any reason to use the piano in performance. The parts are quite easy which supports the idea that this Trio was composed for students.

The trio was also published by Mercury Music in New York, around 1945. There seems to be a typo in the top of each part of this edition, listing the work as for flute, clarinet and bassoon, even on the clearly marked Oboe part and also on top of the score, where the parts are clearly listed as Oboe, B-flat Clarinet and Bassoon. Or, perhaps, Mercury wanted to advertise the work to include flute students as well as oboists.

The First Hungarian Reed Trio – by Sándor Veress

Sándor Veress was born in Hungary in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca in Romania) on February 1, 1907 and died in Berne, Switzerland on March 4, 1992. The first half of his life was in Hungary, the second, starting in 1949 was in Switzerland, but he traveled and taught around much of Europe and in the United States.

In 1923 he began studies at the Budapest Academy of Music, studying piano with Emánuel Hegyi and Bela Bartók, and composition with Zoltán Kodály. His early work included collecting and cataloging folk music in the field and classifying them at the Budapest Ethnographical Museum and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

He was also active as a performer on piano and a composer and his works began being disseminated through performances with the International Society for Contemporary Music Festivals. He performed in Prague, London, Venice, Amsterdam, The Hague, Rome and later Basel, Stockholm, Florence, and Vienna. After World War II he accepted guest appointments in the United States at the Peabody Conservatory, Goucher College, and the University of Portland, as well as Adelaide University in Australia.

The Trio

Sándor Veress’s Sonatina for oboe, clarinet and bassoon was written in 1931 and was published later that year in Milan by Edizioni Suvini Zerboni. The work lasts about 9 minutes. The movements are:

- I. Allegro giocoso

- II. Andante

- III. Grave–Allegrissimo

The East Wind Trio d’Anches has recorded this work and it is available on Spotify. Another version is performed by Nuria Cabezas Castaño, oboe; Paloma Martín Martín, clarinet; and Adolfo Cabrerizo Martínez, bassoon on YouTube (in 3 videos, one for each movement).

According to Catherine McGee Stockwell in “The Oiseau-Lyre Wind Trios”, the French composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud may have heard the premiere of Veress’s Sonatina while travelling to Budapest in 1933, possibly inspiring Ferroud to write his own trio d’anche.

After World War II

Veress was living in Rome when the Communist Party in Hungary adopted the Soviet model of governing. Rather than adapting himself to the political changes, he accepted an appointment at Berne University in Switzerland in the fall of 1949 and that remained his home for the remainder of his life.

In his later life, he developed his own technique of 12-tone composition which developed into a freer serial technique, again, his own. You can hear that in his Diptych for woodwind quintet, but his Sonatina for oboe, clarinet and bassoon predates that by many years.

Veress’s Other Works with Winds

- Dipytych (1968) for woodwind quintet

- Orbis Tonorum (1986) for oboe, clarinet, bassoon, harp, celeste, xylophone, percussion, 2 violins, viola, cello and contrabass.

- Passacaglia Concertante (1961) for oboe and string orchestra (dedicated to Heinz Holliger, one of Veress’s students)

- Concerto for clarinet with harp, celeste, vibraphone, xylophone, percussion and string orchestra (1982)

- Concertotilinkó for flute and string orchestra

- And his final completed work, Tromboniade for 2 trombones and orchestra (1990).

The First English Reed Trio – by Richard Henry Walthew

Richard Henry Walthew was born in Islington in London (Middlesex) on November 4, 1872, and died November 14, 1951 in East Preston, in Sussex.

Walthew studied at the Guildhall School of Music and later was a student of Hubert Parry for four years at the Royal College of Music. He was also friends with Ralph Vaughan Williams. He had early success with a cantata, The Pied Piper, and a clarinet and piano concertos, an Aladdin overture and an operetta, The Enchanted Island. As a composer, however, he seems to have had early high expectations that he later never quite matched.

Chamber music might be where he made the most impact, including a String Quartet in E major, a Mosaic in Ten Pieces for clarinet and piano, and a trio in C minor for clarinet, violin and piano, all performed at a South Place concert on Sunday, November 25, 1900. (Eagle-eyed readers of these pages might remember that the South Place Concerts were where the composer Edith Swepstone had many of her works performed. See her article on our 1930 Roaring Twenties Quintets page.) He is still remembered for his Phantasy Quintet for piano and strings. and his 1932 Triolet in E-flat for oboe, clarinet and bassoon.

Walthew’s Triolet

Walthew’s Triolet in E-flat was written in 1932 (for oboe, clarinet and bassoon) and published in 1934 by Boosey & Hawkes in London. A more recent edition is published in Bradfield, Berkshire, England by Rosewood Publications, www.rosewoodpublications.co.uk .

The movements of the ten minute Triolet are:

- 1. Allegro comodo

- 2. Lento, poco appassionato

- 3. Intermezzo, Allegretto

Walthew’s Triolet in E-flat appears to have been written not for the Trio d’anches de Paris but in spite of it; and it was a long time before another British composer wrote another work for oboe, clarinet and bassoon.

Online, I’ve only found a recording of the first movement of the triolet, performed by an amateur ensemble.

Compared with the works by the French modernists that make up most of the early trio d’anche literature, Walthau’s style is steadfastly conservative. On a trio d’anche concert, however, the Triolet might provide a charming contrast to the pervasive French virtuosic style of the time.

Even by the standards of 1900 England, Walthew was considered a conservative composer, which is probably why he is almost unknown today. Edwin Evans, in an article “Modern British Composer” in the Musical Standard of December, 1903, wrote that “Mr. Richard H. Walthew’s personality is one in which the utmost ingenuity would fail to find a revolutionary element…. Examining his writing from the standpoint of the mere stylist, one is struck by its great refinement and purity, and one would seek in vain for any crudity….”

Other works written by Richard Walthew featuring winds include a Prelude and Fugue (originally for strings) which he transcribed for 2 clarinets and bassoon, a Miniature Quartet for flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon, and a Trio for clarinet, horn and piano. He wrote wrote duo works for clarinet, flute, and bassoon and horn, each with piano.

For an extensive review of the career of Richard Henry Walthew, download the PDF of Peter Atkinson’s summation of his life.

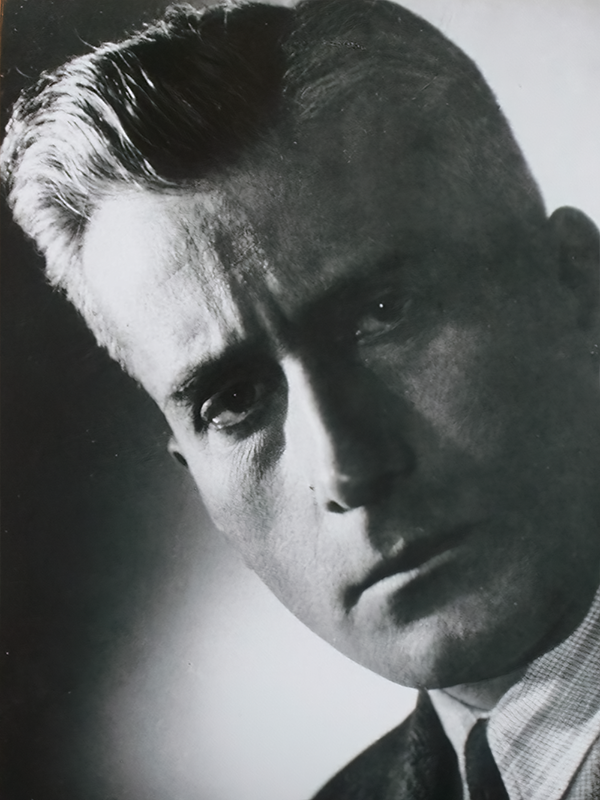

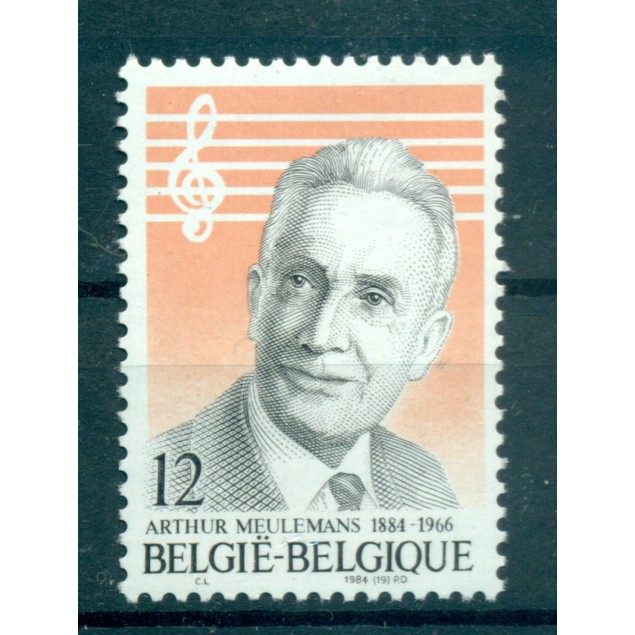

Arthur Meulemans and Another Belgian Trio

Arthur Meulemans wrote his Trio (his first) in 1933 for oboe, clarinet and bassoon. It was published in 1950 in Bruxelles by Éditions musicales Brogneaux. Other than that, there isn’t a lot of information available online and the work doesn’t seem to be readily available.

Meulemans did, however, write a Deuxième Trio (Second Trio) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon in 1960, published in Brussels by CeBeDeM.

Meulemans was born on May 19, 1884 in Aarschot, Belgium and died on June 29, 1966 in Etterbeek, near Brussels.

Meulemans wrote for opera, orchestra, choral groups, organ, strings, and brass bands, but little in the way of chamber music for winds. Besides these trios and an Aubade for wind quintet in 1934, his only other music featuring winds were a number of works for oboe and orchestra and other solos for horn or saxophone quartet with orchestra.

A Belgian trio d’anche ensemble might do well to resurrect, perform and record this work.

Conclusion

We could go on exploring early reed trios not written for or dedicated to the Trio d’Anches de Paris. Paul Gilson and Filip Lazar wrote trio d’anches in 1934, for example. But 1933 seems to be a good cut-off date for this series.

What is interesting about these works is that there was a lot of thinking by a disparate group of composers about the musical possibilities of an ensemble of oboe, clarinet and bassoon. And those composers were not only in France, but Switzerland, Germany, England, Belgium, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Russia, Sweden, and Brazil.

In fact, until the dedication of new works to the Trio d’Anches de Paris, it appears that there may have been nearly as many works for oboe, clarinet and bassoon by Belgian, Swiss and Russian composers as by French composers, a fact other trio d’anche historians or performers may want to study more!

Therefore, it seems that the creation of the trio d’anche school of composition was a truly international effort that started well before the popularization of the Trio d’Anches de Paris. The players in the Parisian ensemble likely had no way to find all of the works that we’ve discussed. But surely they knew (and possibly read and performed) some of them.

What the Trio d’Anches de Paris had going for it was the confluence of recording technology and the support of a single generous patron who would encourage various composers to write for them and then promote those works. It appears that the ability to have their new chamber work performed, recorded and printed all together was a powerful attraction to a number of composers. Also, the Parisian ensemble had the ability and means to tour through parts of Europe to encourage other composers to write similar works.

Coming to maturity in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the Trio d’Anches de Paris made the best of a bad economy by being a small but accomplished wind trio. (They did have active performing careers outside of their trio.) Concert production and touring by three people was much more affordable than by larger ensembles. They were also easier to record in a small studio with a single microphone. Since tape recorders hadn’t been invented yet, most records then were recorded in a single take. Even if they re-recorded a section onto a separate disk, there was no ability to edit the performance. So a smaller ensemble, noted for its performances, would have had an advantage in the recording studio. With their friendship with many of the French modernist composers of the day, they were also called to perform in salons dedicated to new music and in other projects. For example, in 1937, when Darius Milhaud composed music to accompany two French-language productions of English plays by William Shakespeare and John Webster, it appears he wrote the music to be performed specifically by the Trio d’Anche de Paris.

In any case, their longevity as an ensemble helped inspire other reed trios to form and also help promote the oboe, clarinet and bassoon as a viable medium for new works by new composers in France and elsewhere, including in America.

It is no insult to Mssrs. Oubradous, Morel and Lefebvre (the members of Trio d’Anches de Paris), to say that they stood on the shoulders of those who composed and performed reed trios before their own successes. In fact, the scholarly study of the trio d’anche phenomenon is still in its early stages, with many early works still unavailable or unrecorded and many early trio ensembles unrecognized as part of this history.

What is not in debate is that there is today a rich and varied repertoire of music for twenty-first century reed trio ensembles to choose from for performance and recording, going back to the 19th century and continuing today.

Credits

The photo of Paul Pisk is from the American Composers Alliance website.

The photo of the founders of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) in 1922 (including Paul Pisk) is from the Forbidden Music website.

The portrait of Hilding C. Rosenberg is by an unknown photographer, featured in the book Swedish Men and Women (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag 1949), p. 351. Public domain.

Photo of young Karel Albert is from Wikimedia, in the public domain. (It was published in De Katholiekie Encyclopaedie, from 1933-1939.)

Photo of Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov is from the Bakhrusin Museum in Moscow and in the public domain.

Photo of Sandor Veress was taken in 1948 and is available from the Magyar Képszolgálat (Hungarian Photo Service).

Photo of Arthur Meulemans is from the Musicalics website. Interestingly, the Belgian postage stamp engraving appears to be based on the same photo. His article was updated on 11/12/2024 .

Copyright © 2024 by Andrew Brandt