And Much More about Darius Milhaud’s Popular Quintet

Followed by a list of Milhaud’s other works with winds.

A bad translation by a French/American publisher has made the English title of a French quintet a bad joke. But first, let’s start at the very beginning: the movie that sparked the music.

The Conception of Cavalcade d’Amour

In the late 1930s, French film producer Raymond Bernard began working on a movie titled Cavalcade d’Amour. The screenwriter, Jean Anouilh, wrote the dialogue for series of love stories (a curse, two love tragedies, and a final triumph of love), all based in a French castle, the Chateau de Champs on the Loire River. The stories take place in 1639, 1839 and 1939. Since the film portrays three tales in the same location, Bernard hired three composers to write the music for the movie: Roger Désormiére, Arthur Honegger, and Darius Milhaud – one for each Act. Milhaud chose the 1638 scenario of the movie for scoring.

But the War Upsets Everything

The movie was released in early 1940, just before Germany’s invasion of Poland which lead to Britain and France declaring war on Germany. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. German forces entered Paris on June 14, and the French army effectively surrendered in an armistice with Germany by June 22. Bad timing for any cinematic release.

Darius Milhaud, who had grown up in Aix-en-Provence in France, was descended from an ancient Jewish line in that region that dated back many centuries. So after the German invasion, he and his wife, Madeleine (likely with their son Daniel) had to quickly flee the country to America.

The Composition of La Cheminée

Before the war, during the summer of 1939, Milhaud arranged the music of his movie score for woodwind quintet, now titled with the name of King René (1409-1480) who also lived in Aix-en-Provence a few centuries before Milhaud. (Neither King René nor Aix-en-Provence were featured in the movie.) The king referred to in the title is René of Anjou (1409-1480), who was not king of France but briefly King of Naples, as well as Duke of Anjou and Count of Provence. He retired in Aix-en-Provence, where he hosted artists and performers and wrote a treatise on how to hold a tournament. (A history that may have inspired Milhaud’s movement titles.)

Milhaud took the score with him to America and soon got a job teaching at Mills College in Oakland, California, a women’s college (although men could attend graduate classes). So the quintet was premiered, not in Paris, but at Mills College by the South Wind Quintet (possibly a student ensemble) on March 6, 1941. Milhaud gave the work, his Opus 205, the enigmatic title, “Le Cheminée du Roi René.” But it seems that Milhaud didn’t explain to posterity what a proper English translation of the title would be.

Milhaud gave the seven movements new titles, unrelated to their original purpose in the movie (as we’ll see below). The titles of the movements of La Cheminée are:

- Cortège

- Aubade

- Jongleurs

- La Mausinglade

- Joutes sur l’arc

- Chassse à Valabre

- Madrigal nocturne

La Cheminée’s Publication

The quintet was published in 1942 in Cincinnati, Ohio, by Albert J. Andraud, another colorful Frenchman. Born February 17, 1884 in Bordeaux, Andraud was a Conservatory-trained French oboist who toured the United States with the Republican Guarde Band in 1913. When the band returned to tour the United States after the war, Andraud never took the trip back home. He performed oboe with the Chicago Opera, English horn with the Cleveland Orchestra, and landed in Cincinnati in 1929 as principal oboist of the Cincinnati Symphony until 1955. Andraud also set up a small publishing house in Cincinnati which published chamber music and orchestra study books for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn. With his French connections, Andraud became the American publisher for works for winds by French composers. Somehow, Milhaud and Andraud connected and Andraud published the quintet, offering the literal but inexplicable English translation, “The Chimney of King René.”

A few years later, Andraud sold his catalog to Southern Music in San Antonio, which still publishes much of his music.

So, What’s a “Cheminée,” After All?

Early 20th Century American-published French-English dictionaries appear to agree with the Andraud’s translation of cheminée as chimney. My personal paperback French-English Larousse dictionary (many years later) agreed, also offering chemin as “road” or “path.” The legend of King René seems to include a path for his daily walks in Aix-en-Provence on his “chemin.” Cheminé is also a form of the verb, cheminer, “to stroll” or “walk.”

But the title also has some literary associations. The nineteenth century French author, Louis Lurine wrote an 1853 short story, “Le premier bouquet de fleurs d’oranger,” for the literary journal L’Echo des feuilletons. The story referred to “Le Bon Roi René” (Good King René).

Several French journals also quote an old Provençal saying that Milhaud would have learned in his childhood, “se chauffer à la cheminée du roi René” or to “warm up at King René’s fireplace,” which may include a pun of sorts on chimney, fireplace and walkway. Anthony Burton, who wrote program notes for a recording of La Cheminée in 2012, seems to build on this legend, saying that Cheminée refers to a warm, sunny spot in the center of Aix where the king used to stroll, called “King René’s Fireplace.”

Another literary reference is, surprisingly, from Sir Walter Scott’s 1829 historical novel Anne of Geierstein (soon translated into French) with the phrase “King René’s chimney” to describe a feature of the regent’s castle. The British novelist gives the best description of René’s “chimney” in this dialogue between the visiting Englishman named Arthur and Thiebault, a Provençal local:

“I must go to court,” answered Arthur, “without any delay. Wait for me in half an hour by that fountain in the street, which projects into the air such a magnificent pillar of water, surrounded, I would almost swear, by a vapour like steam, serving as a shroud to the jet which it envelopes.”

“The jet is so surrounded,” answered the Provençal, “because it is supplied by a hot spring rising from the bowels of the earth, and the touch of frost on this autumn morning makes the vapour more distinguishable than usual.—But if it is good King René whom you seek, you will find him at this time walking in his chimney. Do not be afraid of approaching him, for there never was a monarch so easy of access, especially to good-looking strangers like you, seignorie.”

“But his ushers,” said Arthur, “will not admit me into his hall.”

“His hall!” repeated Thiebault. “Whose hall?”

“Why, King René’s, I apprehend. If he is walking in a chimney, it can only be in that of his hall, and a stately one it must be to give him room for such exercise.”

“You mistake my meaning,” said the guide, laughing. “What we call King René’s chimney is the narrow parapet yonder; it extends between these two towers, has an exposure to the south, and is sheltered in every other direction. Yonder it is his pleasure to walk and enjoy the beams of the sun, on such cool mornings as the present. It nurses, he says, his poetical vein. If you approach his promenade he will readily speak to you, unless, indeed, he is in the very act of a poetical composition.”

Quoted from the Project Gutenberg ebook edition of Sir Walter Scott’s

Anne of Geierstein; or, The Maiden of the Mist, Volume 2.

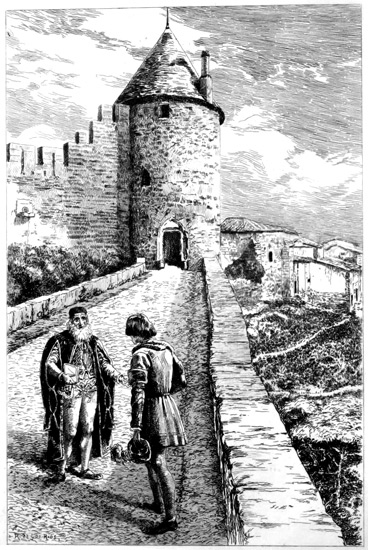

In retrospect, it seems likely that Milhaud was familiar with either Scott’s novel or the legend that Scott drew upon, and adopted the phrase for his title. The later edition of Anne of Geierstein used by Project Gutenberg even includes a romanticized illustration of Scott’s description of the Cheminée, drawn and etched by Ricardo De Los Rios. (Copyright 1894.)

So how does one translate a chimney that is not a chimney? Today’s French-English dictionaries have added “fireplace” to the translation of cheminée. The title “The Fireplace of Roi Renée” and the movement titles of the quintet composition seem to fit well with the image of sitting in either a sunny courtyard by day, or by a cozy fireplace during a cold night while telling stories of knights jousting and medieval life in France. Most new translations of the title (at least the ones that I have seen) call the work The Fireplace of King René.

This isn’t the universal translation for the title, though. Harry Halbreich, in his biography Arthur Honneger (who also wrote music for the Cavalcade), mentions the quintet with the title, King René’s Progress.

But you might be forgiven if you rewrote it as The Promenade of King René, too. (I am tempted, but refuse to call it the Cavalcade of King René for reasons we will see below.)

Milhaud’s Music for Cavalcade d’Amour

As mentioned above, Milhaud’s music was originally written for a movie produced by Raymond Bernard, and directed by Simon Schiffrin with dialogue (in French, of course) by Jean Anouilh. The story line that Milhaud followed lasted for only the first 38 minutes of the production.

I was able to find a source for a DVD recording of the original movie. I spent some time watching and listening to the movie (fortunately with English subtitles, although even I could tell the translation doesn’t always match the French).

Here is an expanded synopsis of the movie’s plot and Milhaud’s contribution:

With other music for the movie’s introductory credits, and then unaccompanied dialogue in the opening scene, you have to wait almost 5 minutes before the first of Milhaud’s music, which is also the opening music to the woodwind quintet, the Cortège. But in the movie it accompanies a wagon of thespians who have just been arrested by armed guards, all moving through the forest until they arrive at the castle.

Milhaud’s next movie music still parallels the quintet, the Aubade, a morning song or serenade, used to begin the bride’s wedding day. However, in the movie it accompanies a group of ladies-in-waiting waking the young bride-to-be, removing a bizarre series of beauty aids from her face, and then going to her prayer desk to pray thanks for the tall, handsome prince she is told she will marry that day. (The music at bar 67 in the quintet’s Aubade accompanies the young lady and her staff saying their prayers). Orchestration-wise, the movie music begins with strings and harp, but it gradually transitions to woodwinds by the end of the scene.

Janine Darcey

The movie continues with a rapid series of scenes without music:

The head of the actor’s troupe meets the bride’s father and learns that rather than being arrested for theft (of rabbits, chickens or trout), they have been summoned to perform a play for the wedding party.

Meanwhile, the bride’s governess informs her ward (the Damsel de Maupré, whose cast name, Julie, is mentioned only once, and might refer to jolie in French) that she has been lied to concerning her groom, the Lord Charles d’Estrac. Although he is royal and young, he is short, fat, not so handsome, has bad teeth, and a pronounced limp. (We will also see that he makes questionable fashion choices, but he’s French, so I suppose it’s allowed.) The beautiful Damsel swallows her disappointment at the news by declaring that love is not as important as the good clothes and jewelry that will enhance her beauty.

Soon the Damsel descends to the castle’s kitchen, where there is mass confusion because the kitchen staff is trying to prepare for the wedding feast while the thespian troupe is trying to rehearse for the play. A handsome, if self-absorbed, young actor called Léandre (played by Claude Dauphin) is struggling to memorize his lines and the Damsel soon ends up giving him his lines when he forgets. Soon, they have a quick argument about the meaning of love and the princess-to-be ends up slapping him in the face and running out. However, instead of reporting his insolence to her father, she orders her lady-in-waiting to bring the actor up to her room, where she ends up ordering him to kiss her. (All of this is without any musical accompaniment.)

The scene briefly changes to show the prince’s own cortège, on the road, with a short trumpet and percussion fanfare by Milhaud (a few bars of music so brief that it never made it into the quintet).

Finally, the royal procession arrives at the castle, with Milhaud’s music that would later become the “Chasse à Valebre” (Later translated as the “Hunt at Valebre,” although the movie is about a hunt for a bride.) Heraldic trumpets announce the theme alternating with strings. (We briefly see two trumpeters playing a fanfare from the ramparts of the castle.) A piccolo briefly enters for a few bars, and the brass fanfare repeats. Movie action also explains the strange ending in the quintet starting at bar 56, where the music changes briefly into 2/4 time with a somewhat discordant clarinet solo. In the movie the same music, buried below the cheers from the crowd, uses pizzicato in low strings and what might be an out-of-tune horn to play the part later given to the clarinet. This music accompanies the young Lord and his mother descending from the coach, with his awkward limp. (In general, the groom is portrayed in somewhat comical form and has no dialogue at all in the movie.) Although the movie music is refashioned fairly literally in the quintet, the instrumentation is completely changed from its cinematic form.

The bride’s father and other members of the castle proceed down stairs to meet the new arrivals (while a friar and the bride’s father still haggle over the price of the girl’s dowry). This is accompanied with music later titled, Jongleurs.

Finally, the prince enters and in just a few seconds the betrothed meet and poof they are wed. (All we see are the wedding rings being removed from their pillow.) With all the theatrical build-up for the wedding, the actual scene is a bust. The only wedding music is a brief, wordless choral accompaniment, although the choral music continues when the bride and her royal groom later travel to the royal bedroom. The choral music doesn’t seem to have any connection to the later quintet. (Although we saw the preparations for the play and the wedding banquet earlier, the actual play and banquet are never portrayed in the movie.)

As the newlyweds are formally seated in their bed, wearing their royal pajamas, all the wedding guests walk through, making their bows and are acknowledged by the couple. The new groom is enthusiastic, but his bride is glum. The Madrigal (Nocturne) makes a prominent turn, featuring oboe solos (instead of flute in the quintet), but most of the music for the scene is sung by a choir (still wordless) with harp accompaniment. (The scene seems bizarre, but then I’ve never attended a French wedding.)

The quintet music at measure 40 of the Madrigal (the quintet’s finale) accompanies the extinguishing of an ornate candelabra and the closing of the curtains of the wedding bed to bid goodnight to the new couple. The music continues with the wordless chorus alternating with winds, strings and harp. Of course, any of the ensuing action that the audience would really be interested in is skipped over in the movie, so no music even hints at it. Instead, we see the theatrical troupe packing up to leave the castle to their next gig. (With string, harp and oboe music never heard in the quintet.)

A quick scene change to later in the evening shows the new groom snoring in bed, while the bride sits awake. Then the movie cuts back to the wagons leaving the castle while the “Cortège” music reprises. Variations on the theme, with some intervening music, occurs while the princess sneaks out of bed and runs to chase after Léandre to escape. But the princess’s absence is soon noticed and a mounted search party looks for her along with dogs, torchbearers, and peasants, eventually catching up with the racing wagon. The young, handsome actor is killed, first by an arrow then beaten with stakes, and the princess, screaming, is recaptured. The entire chase scene is accompanied by the most dramatic music of the story. It’s a shame that none of it appears in the quintet.

Soon, after brief string music, we see the princess, sitting in her wedding bed exactly as before. We might wonder whether she actually attempted escape or if the entire escapade was only in her imagination. In either case, she looks and feels trapped in a life-long unhappy marriage. The story concludes as dawn breaks with French horns and a singer performing a folk song briefly recapping the tragedy of unsettled love. The scene suddenly transitions into the next part of the movie where we now leave, since the other two thirds of the movie have nothing to do with Milhaud’s music.

It is possible that some of the scenes that Milhaud wrote music for were cut or truncated, and other scenes later added, which might explain entire scenes and dialogue without music. This might also explain why quintet music for the movements La Mausinglade and Joutes sur l’Arc are never heard in the movie. But Milhaud was never one to leave his music unused or abused. We don’t know why the composer decided to rewrite the music as his first woodwind quintet or why he brought the score to America. Perhaps it was to be part of a musical résumé for searching for a teaching position outside of France.

In the movie, much of the music is presented in a much faster tempo than is normally performed by later woodwind ensembles. This explains the brisk metronome markings for much of the quintet. But the titles of the quintet music completely change the purpose of the music into a series of medieval court scenes ranging from processions to jousts to pastoral images.

Comparing the music from the movie to the later quintet, one is struck by how flexible the music is in accompanying completely different scenarios. It is fun to see how the music fits with movie scenes, but it is certainly not essential in interpreting the woodwind quintet with its titled movements. Ultimately, Milhaud managed to rescue and resurrect the background music from a (now nearly forgotten) B-rate movie into one of his most popular compositions. It is the woodwind quintet version of the music and it’s implied fairy tale story that has made La Cheminée du Roi René one of Milhaud’s most frequently performed works. It remains a favorite of many woodwind quintets in the twenty-first century in spite of its confusing title.

Other Works by Darius Milhaud for Winds

It’s important to note that Milhaud also wrote a large number of chamber works for winds alone or works with prominent winds with strings, including trio d’anches and other woodwind quintets. In fact, you could probably program an entire season of chamber music from his catalog, making him one of the most prominent classical wind composers from the early twentieth century. You can find even more info on many of these works by looking them up in our quintet, trio d’anche, and winds and keyboard catalogs on this site.

Sonata for flute, oboe, clarinet and piano, Op. 47 (1918), published in Paris by Durand in 1923 and reprinted in 2007. It is now also available from Edition Silvertrust. Although written while Milhaud was in Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian musical style plays no part in the work, although polytonality does. Parts for the original Durand edition are available in those countries where the copyright has expired from the International Music Score Library Project.

Pastorale, Op. 147 (1935) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon. This trio d’anche, dedicated to the Trio d’Anches de Paris, was published in Paris by La Chant du Monde in 1936, and later in Boca Raton, Florida, by Masters Music. This is a very short work with a bucolic feel, but also includes some light satirization of Beethoven’s Pastorale Symphony.

Suite d’après Corrette, Op. 161b (1937) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, published in Monaco by Editions de l’Oiseau-lyre, in 1938 and 1984, is Milhaud’s more famous trio d’anche, based on music by Michel Corrette (1707-1795). It was premiered by members of the Trio d’anches de Paris on a recital for the composer society La Sérénade on November 29, 1938, which also featured the premiere of Auric’s Trio for oboe, clarinet and bassoon. See our entry for the Suite on our Trio d’Anche page for much more info.

Incidental music to Roméo et Juliette, Op. 161 or 161a (1937) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon. This is the source of the music used for Milhaud’s Suite d’après Corrette. The music was written for a French language production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, performed at the Théâtre de Mathurins in Paris. Much more information is also available on our Trio d’Anche page (see link above). It doesn’t appear that the music in this form was ever published.

Incidental music for La Duchesse d’Amalfi, Op. 160 (1937) for oboe, clarinet and bassoon. This music was written the same year as Milhaud’s music for Roméo et Juliette. The music for La Duchesse d’Amalfi (Henri Fluchère’s adaptation of the English play by John Webster) shares the same instrumentation of oboe, clarinet and bassoon. Again, this score appears not to have been published.

Divertissement en Trois Parties, Op. 299b (1958) for woodwind quintet was published in Paris by Heugel & Cie. in 1958, with Alphonse Leduc, as the selling agent. It may also have been published by Theodore Presser in the United States but is not in their current catalog. The three movements are based on music for the Alain Resnais film, Gauguin. This is reportedly a much more serious work than his other chamber music.

Two Sketches for Woodwind Quintet, Op. 227b (1941) was published in New York by Mercury Music Corp. in 1942, with Theodore Presser, being the sales representative. It is now in the Theodore Presser catalog. These two movements are arrangements of the Madrigal and Eglogue, from Milhaud’s Four Sketches for piano.

Quintette pour instruments à vent, Op. 443 (1973) was published posthumously in Paris by Editions Max Eschig in 1975 and in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania by Theodore Presser Company. Milhaud wrote this work for his 50th wedding anniversary with his wife Madeleine. This was his final composition.

“Household Muse” for woodwind quintet and orchestra was published in Philadelphia by Elkan-Vogel, now part of the Theodore Presser catalog.

Scaramouche, Op. 165b for alto saxophone (or clarinet) and wind quintet (transcribed by Don Stewart) was originally for 2 pianos, based on the incidental music to the children’s play Le médécin volant (The Flying Doctor) by Charles Vildrac. It was published in Paris by Editions Salabert in 1975.

L’apotheose de Molière, Op. 286 (1948) for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, harpsichord and strings.

Dixtuor – Symphonie de Chambre (Petite Symphony) No. 5, Op. 75 (1922) for piccolo, flute, oboe, English horn, clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons and 2 horns. Published in Vienna by Universal Edition in 1922 (rental only); and by Kalmus in the U.S., and Mineola (Garden City, New York) Dover Publications in 2001. The score may be downloaded from the International Music Score Library Project. There is a Wikipedia article just for this piece.

Milhaud’s Symphonies de Chambre, numbers 1-3 are for various combinations of winds and strings and may also be viewed on the International Music Score Library Project. (No. 4 is for strings only.)

Concert de chambre pour onze (11) instruments, Op. 389 (1961) for woodwind and string quintets and piano. Published in Paris by M. Eschig, in 1995.

Fin

Credits

The title image of Darius Milhaud in 1923 is by Agence de presse Meurisse. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Milhaud at his desk, in 1926, is by an unknown photographer. It is public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Both the photo of Darius and Madeleine Milhaud and the photo of Igor Stravinsky and Nadia Boulanger visiting the Milhauds are screen grabs from a television interview now in the Institut National de l’audiovisuel in France titled “Darius Milhaud: un petit hommage.!”

The quoted excerpt from Walter Scott’s Anne of Geierstein; or, The Maiden of the Mist, fromVolume 2 and the illustration, titled “King René” by Ricardo De Los Rios are from Project Gutenberg. The digital transcript is from the edition of the novel printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. in Edinburgh, Copyright MDCCCXCIV (1894). In the public domain.

Movie stills from Cavalcade d’Amour are screen grabs from a DVD of the movie, made available from MovieDetective.net.

Copyright © 2025 by Andrew Brandt