The Critical Decade for the Woodwind Quintet

The (Original) Seven Composers

Those seven composers in our 2016 article were Paul Hindemith, Carl Nielsen, Arnold Schoenberg, Theodor Blumer, Heitor Villa-Lobos, Oscar Lorenzo Fernandez and Jacques Ibert. The works that they composed at this time include some of the most famous works written for quintet.

In my original article on the Roaring 20’s Quintets, I called these composers The Seven or Les Sept, but that was my first mistake. Since I first published my article, further research on quintets during these years finds an additional 52 woodwind quintets by 49 composers. (To put that number in perspective, 56 composers (in the years 1920-1930) exceeds the number of all known woodwind quintet composers before 1920. [Updated 11/18/2024]

Also important is the fact that each of these pieces is in a distinct musical style. This broadened the appeal and perception of the woodwind quintet and showed that composers can use the woodwind quintet for almost any style of music they can come up with. In the century since the 1920s, the number of composers writing woodwind quintets has expanded exponentially and still continues to grow today. Without these 1920s composers, though, the woodwind quintet might be more of a chamber music curiosity than a more mainstream ensemble.

Now, in the 2020s, we also find these older works are in or will soon be in the public domain, so easily getting study scores and parts for several of them is possible online, particularly through the Canadian music site, the International Music Score Library Project (also known as the Petrucci Music Library). All of the seven works are still in print, some in new editions or available for download.

A look at the specific works should, I believe, confirm the thesis that the 1920s changed the woodwind quintet. A series of concerts (or recordings) specifically of these works would be a great project for a professional quintet, too, to celebrate their centennial.

The Chrysler Building was a prime example of the Art Deco period of architecture in the U.S.

What is so Special about the 1920s?

The world breathed a great sigh of relief after the World War ended in 1918. (Not least the composers Hindemith, Ibert and Ravel and others who served during the war.) Real relief had to wait, however, until the end of the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918-1919, which killed around 50 million people worldwide (including about 675,000 in the U.S.). So the 1920s became an age of relief, prosperity and celebration.

1920s Fashion, Technology, and the Arts

The 20s flapper redefined womanhood and fashion. Women campaigning for the vote succeeded in most major democratic countries, upending politics. But technology, media, and art also quickly changed the world during the decade.

Technology redefined communication, travel, art and music with the mass manufacture and distribution of automobiles, movies, recordings, radio, and commercial passenger airplanes. Consumer demand led to record industrial growth, and we also suddenly had movie stars, famous athletes and popular singers. It was also an age of financial speculation, which ended abruptly in the Stock Market Crash from October 24-29, 1929.

In the arts it was a time of discontinuity and change. Jazz and popular dance became more important. The Charleston, the foxtrot, the Lindy hop, and the tango took over popular dance. A few of the popular musicians of the age were Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Paul Whiteman, Bessie Smith, Jimmie Rodgers, George Gershwin and Bing Crosby.

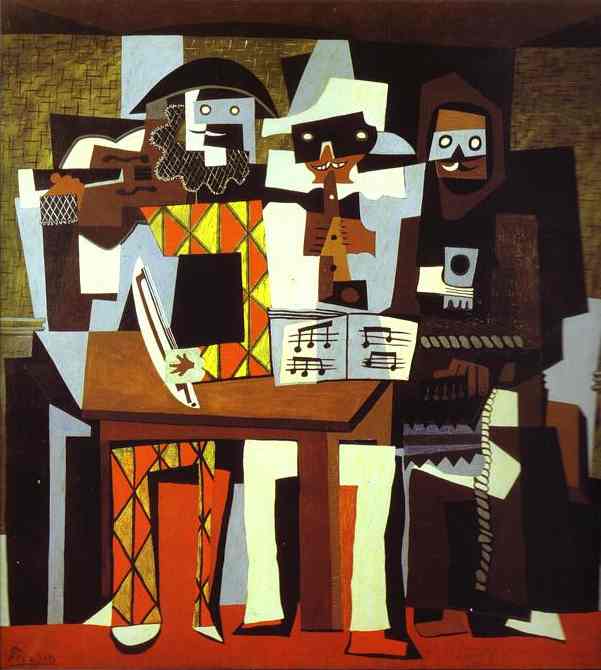

Art Deco influenced design in the 1920s. So did Expressionism, Cubism and, later, Surrealism. Both sound and color came to cinema. Felix the Cat and Mickey Mouse made their debuts, as did the use of newsreels. In New York, the Harlem Renaissance brought literary and artistic liberation to many African-Americans, although some eventually left for Paris to escape racism.

In classical music, there was a great deal of musical change before the World War (the most famous being Stravinsky’s ballets). But the rate of change sped up even more afterward, with the Second Viennese School promoting 12-tone music and Les Six reacting hard against it in France, and new national movements developing around Europe and in the United States, Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico.

Here Come the Americans

In 1921, the French Music School for Americans opened in Fontainebleau. One of the instructors was Nadia Boulanger, who was to become famous in her own right as a teacher and conductor. One of the first students to walk in the door was Aaron Copland and soon there was a stream of American composers and conductors trying to meet Boulanger’s strict standards in ear training, performance and composition. (George Gershwin tried to get into the school, but famously, Boulanger told him, “I can teach you nothing.” Gershwin thought it was a compliment. Many others thought not.)

Just of few of Boulanger’s other American students over seven decades included Roy Harris, Quincy Jones, John Eliot Gardiner, Elliott Carter, Virgil Thomson, David Diamond, Daniel Barenboim, Phillip Glass, Robert Russell Bennett, Donald Erb, Robert Kapilow, Thea Musgrave, Daniel Pinkham, Walter Piston, Elie Siegmeister and Astor Piazzolla. Many of them would later make their contribution to woodwind quintet literature, too. During lecture tours in the United States, Boulanger also became the first woman to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Washington National Symphony. Many of Boulanger’s other students also became academics in the United States, teaching generations of music students. Of all the music teachers around the world, few, if any, had the impact on music education and creativity in the USA as this woman who mostly taught out of her family’s flat in Paris.

What Caused this Sudden Surge of Composing for Woodwind Quintets?

The still unresolved question is, why did the number of people writing woodwind quintets increase so much in the 1920s? I have a few theories. I’ll mention them now so you can think about them as you read on.

1. There had to be composers writing quintets and there had to be quintet musicians ready to perform them. (The chicken and the egg problem, which came first?) Were more quintets being written just because there were more woodwind ensembles, or were there more ensembles because composers were writing more quintets? Neither happens in isolation.

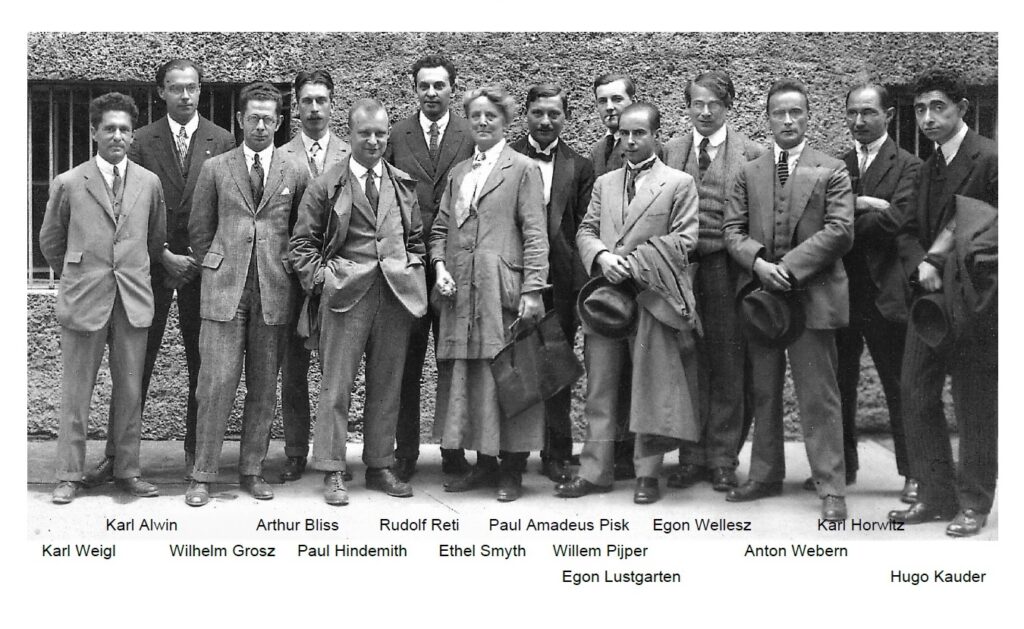

2. In 1922, a new group for composers and musicians was formed in Salzburg, the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM). It’s first annual festival of contemporary music (now known as ISCM World Music Days), was in 1923 in Salzburg. With surprising speed, nearly every country in Europe would have its own chapter. It was successful, in its annual meetings around the continent, in sharing info and music of the most avant-garde and merely modern compositions. I see no smoking gun, but the rise of the ISCM and its educational and promotional programs unexpectedly parallels the new rise of popularity of the woodwind quintet. Many of the early proponents of the ISCM were supporters of the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Berg and Webern and their students and friends), and Arnold Schoenberg’s first multi-movement work in 12-tone style was his one and only woodwind quintet. Other composers who appear to be active in the earliest years of the ISCM include Paul Hindemith and Willem Pijper, who both wrote quintets in the ’20s. Did the early members of the ISCM promote the use of the woodwind quintet in any way? I have no direct evidence. (This is the kind of question that doctoral theses could be written on. Go for it.)

There are many dictionary articles about the founding of the ISCM, but a very different discussion of 1920s political and cultural conflict at the founding is on the Forbidden Music Website, An International Music Society that was both “New” and “Contemporary.” More information by the same author about the ISCM is included in a parallel article, The Centenary of the Salzburg Festival.

This photo shows composers who met in Salzburg in 1922 to form the International Society for Contemporary Music. Five of the composers in this photo would go on to write woodwind quintets: Hindemith, Paul Amadeus Pisk, William Pijper, Egon Wellesz, and Hugo Karder. Arnold Schoenberg would soon be active in the group, also. From the Forbidden Music website.

3. Or maybe it was Technology, Teaching and Timbre. It could be the improvements in woodwind and horn construction and teaching over the previous 100 years made the woodwind quintet, by 1920, an attractive exercise in combining different timbres, techniques, and styles into a single composition (unlike a string quartet where the timbres and techniques are mostly the same for each instrument). Seeing this, composition and orchestration teachers now started encouraging their students to write for this ensemble as a test or exercise. Two of Schoenberg’s students are included in this list, writing about the same time Schoenberg was completing his own woodwind quintet. In the 1920s, we may be seeing the beginning of composition students writing a woodwind quintet as part of an academic thesis or lecture or composition recital—a practice that continues today.

4. In parallel with the previous idea. Perhaps, with the end of the Romantic and Post-Romantic styles of writing, composers were more interested in combining diverse instruments and timbres as solo instruments, rather than creating a blended harmonic structure (as in the Harmoniemusik school of wind writing). The woodwind quintet was now a ready-made tool to explore, even for students. Parallel to this change in music was the creation of live radio broadcasts and 78-rpm and later 33-rpm records. Perhaps the tonal qualities of the woodwind family were particularly easy to distinguish over early broadcasts (and easier to record than larger ensembles) and appreciated by audiences. The creation of improved, electric microphones during the ’20s was a critical technical improvement (for both radio and the recording industry), just as tape and stereo recording would be in the 1950s.

5. Part of the big growth of the woodwind quintet in the 1920s might also be as simple as geography. Many of the composers working in this new-ish medium were from places that promoted wind instrument performance. Paris is the prime example: the French had over 100 years of promoting compositions for winds (from Anton/Antoine Reicha forwards). They already created a number of groups to promote music for wind instruments (and had already commissioned or promoted works for earlier woodwind quintets). Other cultural centers, such as Vienna, Budapest, and Prague also had a history of promoting music for winds. (Other cities, such as Amsterdam, Rome, Brussels, Madrid, and Warsaw had less of a history of wind instrument building and instruction, and we find fewer of our composers from those cities.) As more (primarily) French musicians traveled to Boston and New York as well as Chicago and Los Angeles, they also promoted wind ensembles, including the quintet, to the United States and, indeed, we find more American composers writing for woodwind ensembles in the ensuing years. In the 1930s, as more composers from all over Europe landed in the United States, the music schools here began producing more composers who wrote for woodwind quintet. (I think I’ll call this The Steamroller Theory.)

6. Or maybe I’m just over-analyzing it. The woodwind quintet was just a natural extension of existing musical trends. But what caused those trends to trend that way? Or maybe it’s a combination of all of the above trends coalescing at the same time.

We will have articles about all seven works listed above. We will also begin looking at all the 1920s composers in our series, listed by year of composition, starting with 1920.

Credits

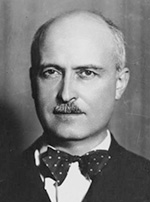

Pablo Picasso’s Three Musicians, painted in 1921, is a good example of cubism. Picasso painted himself as the violinist, wearing a Harlequin outfit with bright red and yellow triangles (the colors of the Spanish flag). The center character, in white, is the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had recently died of wounds he received in the World War I. The third musician is poet Max Jacob, in the brown monk’s robe, marking his decision to join a monastery.

The Chrysler Building in New York City. Photo by the author, Andrew Brandt

1920s fashion photo – Actresses at Mary Pickford’s Tea Party.

1924 Model T Ford. The Model T was affordable and became the mode of travel for millions.

Nadia Boulanger, music teacher and conductor. Photographer unknown.

Photo of founding members of the ISCM is from the Forbidden Music Website.

Copyright © 2024 by Andrew Brandt