A New Viennese School

Arnold Schoenberg was a composer, a theorist, a conductor, a teacher extraordinaire, and probably a genius. Few composers have so consistently attracted admiration from a wide variety of musicians (sometimes grudgingly), and also so consistently been avoided by audiences.

Of all the pieces in our exploration of the woodwind quintets of the Roaring 20s, none of them is as historic, as complex or as long as Schoenberg’s Quintet, Op. 26. Trying to write about it is also a challenge. Let’s see if we can tackle it together.

Schoenberg’s Long Path

It may surprise some readers that Arnold Schoenberg (born Arnold Franz Walter Schönberg on September 13, 1874 in Vienna, died July 13, 1951 in Los Angeles) was a Romanticist before becoming a musical revolutionary. Chamber music was also a significant medium for him to work out his artistic and theoretical ideas. A listener needs only to listen to Schoenberg’s 1899 string sextet, Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night in English) to get a sense of his hyper-Romantic style. He attracted the attention and admiration – at least for a while – of both Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

It was when composing his earlier works that Schoenberg began pushing against the tonal limits of the Romantic style.

For readers who are not music theorists, it helps to know that from the time of Beethoven, in the late 18th / early 19th centuries, to the time of Mahler (well into the 20th century), there was a gradual expansion of the use of additional and complex harmonies, or chords. With these more complex harmonies, it also became easier to move from one key to another. Eventually, for some compositions, it became harder to figure out which key the composer was actually thinking of when moving from one key center to finally arriving at another.

At first, Schoenberg embraced these Romantic extensions, pushing them even further than composers like Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss were willing to go. Finally, Schoenberg began to go beyond to a new chromatic system of harmony in works like his String Quartet No. 2, Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, and his massive Gurre-Lieder for five vocal soloists, narrator, three choruses and large orchestra.

Finally, Schoenberg envisioned a new post-Romantic way of writing music that treated all the 12 chromatic tones in an equal fashion, eliminating the need for key signatures, and jettisoning traditional thinking about harmony. Yet, Schoenberg did not see this as a break from Romanticism, but its logical next-step. Other composers agreed with him and, with Alban Berg and Anton Webern, they developed what became known as the Second Viennese School (the first Viennese School being the world of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven).

But, moving from theory to large-scale musical composition still took Schoenberg a while. It wasn’t until 1923 to 1924 that he wrote his woodwind quintet, his first multi-movement work based on a single 12-tone row. Clocking in at about 40 minutes, the work is complex and technically challenging for the players. (When performing with the Shreveport Symphony Woodwind Quintet, we decided to tackle Schoenberg’s work and spent 20 full rehearsals just learning the one piece. We could have taken more, easily, but we had a scheduled concert to play.)

For those readers who have not studied a great deal of music theory, let’s back up a bit and discuss what Schoenberg did for music.

What is All This Stuff about 12 Tones?

A Brief Lesson in How 12-tone Music Works

For those not familiar with 12-tone composition, the basic idea is to liberate music from traditional harmony by treating all 12 chromatic tones equally and ditching the “old” tradition of writing in specific keys.

If you look at a piano keyboard, think of playing all the keys, black and white, from C to the next higher B. Those are the 12 pitches every composer uses. Take those 12 notes and mix them up into one fixed order (no fair repeating any of them). Then transpose some of the notes into different octaves (same note, just in a different part of the keyboard). Instead of a scale or a chord, you now have a “tone row” series of 12 different notes. (Many musicians call this style “serial music,” which is a term that Schoenberg detested.) Although a single note may be repeated, the composer cannot return to it until he or she has exhausted all the other notes of the row, either melodically or harmonically.

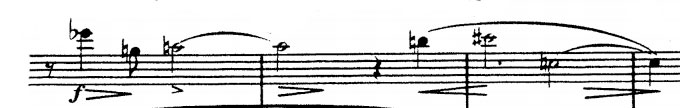

To simplify even further, let’s look at a half of a row of six notes: E♭, G, A, B♮, C♯ and C♮. (If your web browser shows you weird characters instead of sharps and flats, that’s: E-flat, G, A, B, C-sharp, C-natural.)

Now, instead of the specific note names, think of the intervals between the notes. From E♭ down to a G is a minor sixth. Then an A (up a whole step); then B (up a whole step); then C♯ (up another whole step); then down to a C♮ (down a major seventh). These are the actual first six notes that Schoenberg uses in his Quintet’s tone row.

Now that you know the intervals between the notes, you can easily turn the intervals upside down. In the previous paragraph, use the same intervals, just switch “up” with “down” and vice versa. This creates a mirrored image with the same intervals.

You can also play these notes backwards, which is called retrograde (or “cancrizans,” meaning “crab-like”).

You can also transpose these intervals by starting with any other note, but keep the intervals the same. Then you can play that backwards or upside-down, too.

There are other ways to manipulate these intervals. For example, when you have all 12 tones of the row, you can divide the first six notes from the second six notes, and rotate each group of six. This is like taking each 6-note group and playing each backwards, one after another. (Schoenberg actually does this in his quintet.) You could also divide the 12 tones into groups of four, or three, or two and manipulate each of those groups.

Since the tone row is the defining feature for a piece, a composer normally creates a new row when writing a new work.

If you’ve been able to follow me so far, you can see how 12-tone music is a very mathematical concept as well as musical. Some composers have found this dispassionate idea of manipulating notes very attractive. Others think it sucks all the emotion or creativity out of a piece of music. That’s why it’s still controversial.

Let’s get back to the Quintet, now.

The Composition of the Quintet

Quintet, Op. 26

- I. Schwungvoll [Lively]

- II. Anmutig und heiter—scherzando [Graceful and cheerful—scherzando]

- III. Etwas langsam [Somewhat slowly]

- IV. Rondo

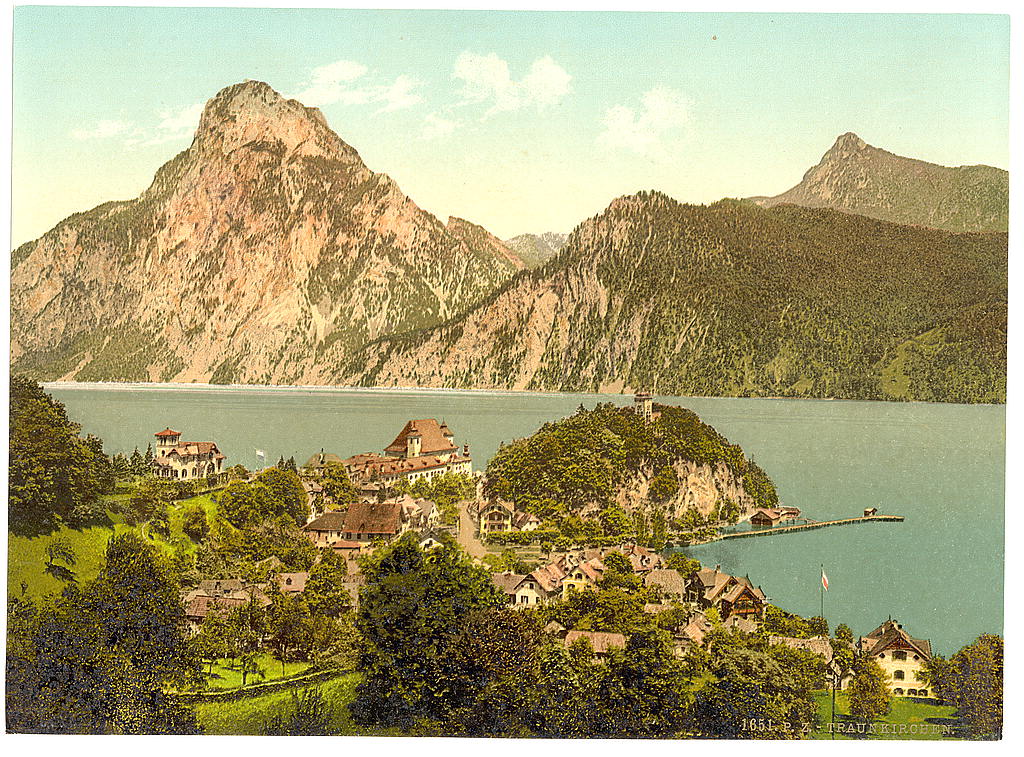

Schoenberg had a non-musical tragedy while composing this work. He began composition of the work on April 14, 1923. He completed the first movement on the evening before he and his family arrived in Trauenkirchen, Upper Austria, on June 1st. He wrote on the manuscript, “I think Goethe would have been quite happy with me.” (This might make more sense to a student of German literature and culture than to most Americans today.)

Over the course of the summer he worked on the quintet as well as several theoretical and historical writings. But his work was interrupted by the illness of his wife, Mathilde. In September they returned to Vienna where she was admitted to a sanatorium. She died on October 18, 1923. Although their daughter was already married, Arnold was now the sole parent to a teen-age son. In mourning, he was unable to return to work on the quintet until the next summer.

Schoenberg’s fortunes began to change in the spring of 1924 when he became good friends with Gertrud Kolisch, the sister of one of Schoenberg’s pupils. The friendship grew and resulted in their marriage on August 28, 1924, notably a day after he completed work on his Quintet. He dedicated the work to his young grandson, “Bubi” Arnold.

So, Schoenberg finished his Quintet a few days before the age of 50, a bit old for starting a revolutionary new style of composition and steering one’s compositions into an entirely new direction.

In a much more personal way, the Quintet also spans two marriages. Although we have little biographical material discussing his personal feelings, perhaps Schoenberg was compelled to finish the Quintet, something he started before Mathilde Schönberg died, on the day before he wed Gertrud to start a new chapter in his life.

Schoenberg’s son-in-law, Felix Greissle conducted the premiere performance of the work, on September 13, 1924 (for Schoenberg’s 50th birthday), probably in Vienna, although info about the performance and the ensemble is non-existent, at least on the web. With the performance coming just 16 days after the work’s completion, one wonders how much time the first ensemble had to learn the piece. The tight schedule might explain why they decided to use a conductor.

A Brief Analysis of the Quintet’s Tone Row

Don’t worry, this won’t get too technical. (There are people who have done a precise note by note dissection of this entire work. – I am not one of them.)

The first six notes of the Quintet’s 12-tone Row are easily heard in the flute in the very beginning of the work:

The next six notes are also easy to hear, but several measures later, in the oboe:

What is interesting is that Schoenberg designed the second half (notes 7-12) of the row to use the same intervals as the first group (except for the last note) – just starting a fifth lower. Also interesting is the second, third, fourth and fifth notes of each half outline four notes of a whole-tone scale (familiar to listeners of Debussy). In fact, using each half of the row, there is an inherit scale pattern that attempts to simplify the difficulty of listening to the work. Many later 12-tone composers sought to avoid any hint of a scale or chord in their constructions. Schoenberg embraced it, at least in this work, and used this row in all four movements.

The Formal Construction of the Quintet

If Schoenberg was revolutionary in his use of the tone-row, he was, in a way, conservative in its formal structures.

Schoenberg wanted to preserve some of the traditional musical forms, even as he changed melody and harmony. (Remember, he thought this was an extension of earlier music, not a complete break from it.) But to preserve the old formal structures (which were largely based on traditional melody and harmony), he had to redefine them.

The first movement is based on the “sonata-allegro” form. The sonata-allegro form was developed in the Classical period (by Haydn and Mozart and Beethoven among others), developed through the course of the Romantic period (Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Brahms and many other composers), and reused by many 20th century composers in the “neo-classic” style. (Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony is one famous case in point, as is the Carl Nielsen Quintet we examined earlier in this series.)

Where Schoenberg differed in his use of sonata-allegro form (and the other forms he uses) is that he doesn’t require the form to be based on traditional melody and harmony. After all, the 12-tone method was designed to break away from that “tyranny.” But the form is there and is easily recognizable with study.

If one takes the musical forms in his Quintet by themselves, they are as conventional as a quintet by Franz Danzi. Obviously the execution is as different as can be.

Likewise, the 2nd movement of the Quintet is in the form of a scherzo (seemingly a parody of a waltz, at least to my ears). In fact, since the term “scherzo” is often translated as a “joke,” Schoenberg appears to throw a joke into the works when, while the other players are engaged in 12-tone counterpoint, the bassoonist suddenly presents the bass of a very traditional V-I (dominant chord to tonic) cadence, fortissimo, before rejoining the 12-tone fray (see bars 56-57). Did Schoenberg have a sense of humor? I would argue yes, but he hid it well.

The 3rd and 4th movements also reflect traditional musical forms, the 3rd being a slow movement with a simple ABA form and the finale an extended rondo in A-B-A-C-A-B-A form.

What About the Listener?

By now, you are probably asking how you, a listener to this work, are supposed to recognize which of these tone-row variations is in play at any given time. The answer is, you can’t. Even a music theorist with perfect pitch and lots of experience in analyzing 12-tone or “serial” compositions would be hard-pressed to do their analysis by ear alone.

In fact, it’s this divide between the theoretical aspect of 12-tone music and its aural appreciation that is the hardest part of listening to this or any 12-tone work. As the 20th century progressed, it was a musical divide that most audiences (and many musicians) decided not to bridge, even though composers, such as Schoenberg, believed that with practice a listener could develop some recognition. That is why Schoenberg thought his system was both a theoretical and a natural progression from the harmonic “excesses” of the late Romantic period. Obviously, many composers as well as audience members disagreed with him.

Now, well into the 21st century, few “classical” composers wholeheartedly embrace the 12-tone style of composition for their career. But they have almost all studied it, often in depth.

This quintet is challenging for the performers, too. Even if each performer were to take the time to analyze the 12-tone variations of the opening row, that doesn’t help solve the many technical and musical problems that he or she needs to solve for this (or any) composition. Yet, many performers have decided to tackle this piece at least once in their career, and there are rewards (musically and in “bragging rights”) for those who do.

Since the 1920s, there have been an uncounted number of woodwind quintets written using variations of Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique, some going well beyond the ideas that Schoenberg applied to his work. None of them has been performed or recorded as often as the very first one that Schoenberg created.

Where to Find the Quintet

The Quintet, Op. 26, is still published in Vienna by the Universal music publishing company.

The score and parts are also available for free download, in those countries where the copyright has expired, from the International Music Score Library Project. Finished in 1924, Schoenberg’ s Quintet is now in the public domain in the United States. In other countries, presumably, the fair-use doctrine should apply to educational use of the score, but you should rely on a copyright attorney or librarian, not this author, to decide if that is really the case.

Opus 26 is Schoenberg’s only woodwind quintet. It’s curious that he chose this medium for such a historic piece. At the publisher’s request, the Quintet was arranged by Felix Greissle (Schoenberg’s son-in-law) for Violin or Flute or Clarinet and piano and also for Piano, 4 hands, in the hopes of popularizing the work more.

The only other Schoenberg work for winds that I’ve found is his Theme and Variations for Full Band, Op. 43B of 1943. (He also wrote an orchestra version.)

Over 20 commercial recordings have been made of the Quintet. There were two discographies available online back in 2016 from both the Schönberg Center and Wikipedia (links below), but the Schönberg Center website seems to have removed their version. The Wikipedia discography remains. Presto Music also has a collection of current recordings.

Listening Online

The Austrian Arnold Schönberg Center has a sound recording available on their website. Unfortunately, it’s an anonymous recording.

There are a surprising number of recordings of this work available for listening on YouTube:

A notable but anonymous recording allows you to follow along with the score while the quintet is playing. This is particularly valuable for those who are learning the work for performance (or analysis). It’s also a complete performance in one file, whereas most YouTube recordings are listed by movement. (If anybody can identify the ensemble, please tell us in the comments, below.)

A recording by the Vienna Wind Soloists is available, with Wolfgang Schulz, flute; Walter Lehmayer, oboe; Peter Schmidl, clarinet; Volker Altmann, horn and Fritz Faltl, bassoon. It was recorded for Deutsche Grammophon. Each movement is listed separately: first movement, second movement, third movement and the fourth movement.

A live video recording of the work features a young quintet with performers: Irene Kavcic, flute; Alexandre José Bocalari, oboe; Tommaso Lonquick, clarinet; Jorge Monte de Fez, horn and Amber Mallee, bassoon. The performance dates from 2010 and was recorded at the Escuela Superior de Musica Reina Sofia in Madrid. This is the only live performance of the Schoenberg that I found on YouTube.

One of the earliest recordings of the Quintet, Op. 26, was by the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet. A re-mastered version of 2023 is now available. Performed by William Kincaid (flute), Anthony Gigliotti (clarinet), John de Lancie (oboe), Sol Schoenbach (bassoon), and Mason Jones (french horn). First movement; Second movement; Third movement; and the finale.

A fine 1977 recording by the Wiener Bläsersolisten on Deutsche Grammophon is also on YouTube. Again, the movements are separated, with the first movement; second movement; third movement; and the fourth movement. Although not listed on YouTube, the musicians are Wolfgang Schultz, flute; Walter Lehmayer, oboe; Peter Schmidl, clarinet, Fritz Falti, bassoon; and Volker Altmann, horn. (One of my pet peeves on YouTube is when they carefully list all the recording engineers and producers for their recordings, but omit the performers’ names, as is the case here. A web search for the LP recording reveals their names.)

Another sound recording available (not on YouTube) is that of the Soni Ventorum Wind Quintet, originally recorded for the Musical Heritage Society in 1992, now available via a creative commons license (non-commericial, attribution) on the International Music Score Library Project website. The performers are Felix Skowronek, flute; Alex Klein, oboe; William McColl, clarinet; David Kappy, horn, and Arthur Grossman, bassoon. (You can play the four audio files online or download them and use a media player to listen to them. You can also download the PDF score to follow along.)

Flute players might be interested in the official flute and piano version of the work (with piano four-hands). (You may need to hunt for the other movements.)

Credits, References & More Info

The Arnold Schönberg Center has a great deal of info about the composer’s life and works, including a page about the Quintet written by Therese Muxeneder.

The Wikipedia article on the Quintet offers an alternate theory of the construction of the work’s tone row as well as more info about the work and a discography of 16 recordings of the quintet.

Program notes by Felix Skowronek for a performance by The Soni Ventorum quintet includes an analysis of the tone row for the Quintet and a history of that quintet’s return to the work. The link automatically downloads a PDF of the original program and notes.

Advanced Analysis

Symmetrical Partitioning of the Row in Schoenberg’s Wind Quintet, Op. 26 by John Maxwell is an advanced analysis of the use of the tone row in Op. 26 that requires a reader who already has some familiarity with tone row analysis. (The link automatically downloads a PDF of the article.)

Comprehending Twelve-Tone Music as an Extension of the Primary Musical Language of Tonality by Graham H. Phipps is part of the College Music Symposium website.

Reevaluating Twelve-Tone Music Analytical Issues in the Second Movement of Anton Webern’s Quartet for Violin, Clarinet, Tenor-Saxophone and Piano, Op. 22 by Tzu-Hsi Lin, University of North Texas, 2006. In the first chapter, the author notes similarities of the Quartet with Schoenberg’s Quintet and how Webern studied Schoenberg’s Quintet while working on his own work. (This is also a PDF download link.)

Photo credits

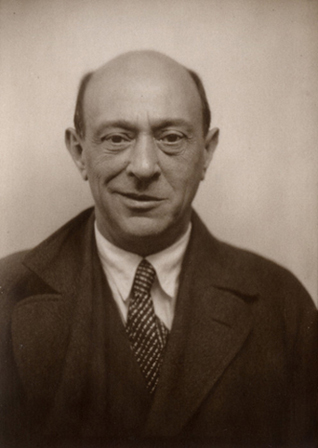

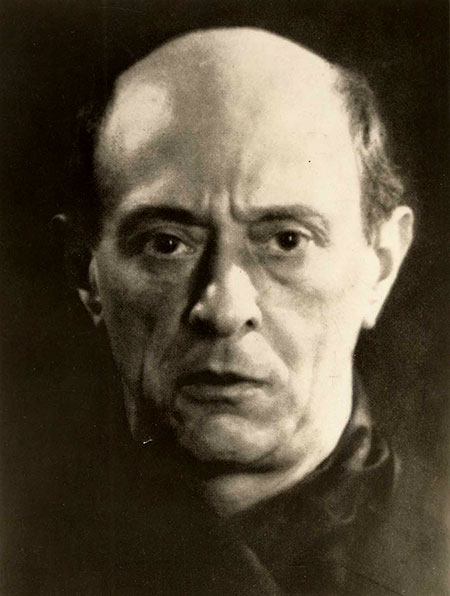

Smiling (smirking?) Schoenberg portrait was taken circa 1926 and shared by the Arnold Schönberg Center.

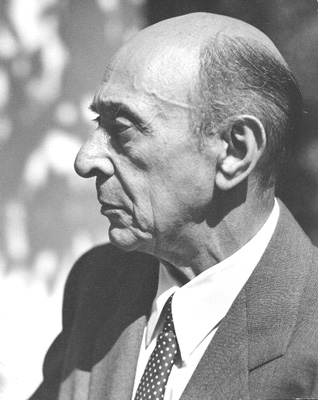

The Schoenberg side-profile image is from Wikipedia and is widely used around the web. Unfortunately, the photographer is not listed.

Print of “Traunkirchen, towards the Traunstein, Upper Austria, Austro-Hungary,” where Schoenberg did early work on his Quintet, Op. 26. Image is from the Detroit Publishing Co., foreign section, circa 1905. From the catalog of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Stern front view of Arnold Schoenberg is from a photo by the American-born, Parisian-based, experimental photographer, Man Ray. Dated 1926.

Copyright © 2016 – 2024 by Andrew Brandt